Shipping companies, like people, often crave publicity, to increase their popularity, prestige and crucially in the case of the former, passenger numbers. Sometimes however the publicity is unwanted. Santa Maria will always be associated with the hijacking in January 1961 and perhaps inevitably that single episode dominates a career spanning twenty years. Nevertheless, irrespective of this infamous event, Santa Maria and her older sister Vera Cruz were noteworthy ships, fully deserving their place in the annals of ocean liner history.

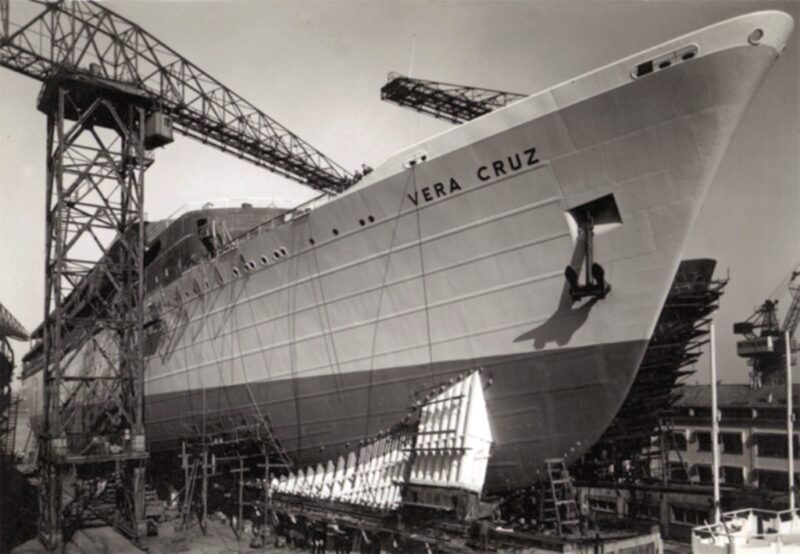

The new vessels were part of a government driven initiative formally called the ‘Naval Trade Renewal Plan‘ but generally referred to as ‘Despacho 100‘ (Dispatch 100). This was a program devised by the Portuguese Naval Minister Amérigo Thomás to rebuild and expand the nation’s merchant marine in the aftermath of the Second World War. As a neutral country, Portugal and it’s shipping lines had built up significant financial reserves during the conflict and Thomás’ ten year plan was a conduit for this investment. Ultimately the plans resulted in the construction of 56 new vessels of various types (mainly freighters), slightly fewer than the intended 70 target. At over 20,000grt the two new liners were the largest individual units included in the initiative. They were ordered by the nation’s principle transoceanic shipping line, Companhia Colonial de Navegação (C.C.N.) in August 1949 and contracted to the Société Anonyme John Cockerill shipyard at Hoboken, Belgium, which duly allocated them yard numbers 748 and 749. The keel of the first ship was laid on 13th May 1950 and she was launched as ‘Vera Cruz’ by Gertrude Thomás into the River Scheldt just over a year later, on 2nd June 1951. Much of her superstructure carcass was already installed at the launch and indeed this facilitated her rapid completion, being commissioned by C.C.N. on 23rd February 1952.

After expending 86,000 man hours John Cockerill delivered a magnificent looking vessel, the largest to have been built in Belgium. With a length of 185.9m (610ft), breadth of 23.1m (75.8ft) and draught of 8.44m (26.4ft) the 21,765grt Vera Cruz was the largest Portuguese passenger ship to date when she sailed up the Tagus to be greeted by government dignitaries on 2nd March 1952, departing Lisbon on her maiden voyage to Buenos Aires eighteen days later. Amongst her passenger list was a trade delegation including the navigator, cartographer, historian and naval officer Admiral Gago Coutinho, fellow officer and politician Rear-Admiral Henrique Tenreiro, former colonies minister Teófilo Duarte and the actress and singer Hermínia Silva. Not for the first or last time a national flagship was used as a prestigious extension of the country she represented, in this case a potent symbol of Portuguese confidence. Her arrival in Rio de Janeiro on Saturday 29nd March 1952 is remembered as amongst the greatest ever afforded any ship of any nationality. With thousands lining the shore and a myriad of ships, boats and almost anything that floats escorting her in, Captain Hilário Filipe Marques exchanged greetings with the huge flotilla as celebratory rockets and fireworks exploded overhead. Once the early fog had dissipated Vera Cruz docked in the early afternoon. In the course of her stay she hosted a dinner for the Brazilian president Getúlio Vargas, before sailing on for an equally overwhelming welcome at Santos before calling at Montevideo and ultimately Buenos Aires.

Six months later the 20,906grt Santa Maria was launched at the same Hoboken yard, joining Vera Cruz on the South America service in September 1953. Although they shared the same dimensions there was one notable difference between the ships, the Santa Maria’s open promenade on A deck wrapped around the First Class Smoking Room, whereas the same room extended across the whole width on her sister. As a result Santa Maria’s forward facing bulkhead was broken up and more distinctive than that on Vera Cruz.

Externally the ships had a rather noble demeanour, concealing well their most distinctive feature, the heightened superstructure. The use of aluminium with its weight saving properties was only just gaining prominence in mercantile ship construction, most famously with the Blue Riband winning United States. So proud were C.C.N. of their ships’ innovative construction that slithers of the alloy were included in publicity advertising packs. In other respects the ships featured a typical post-war silhouette, a solitary mast was positioned atop the bridge, a central, well proportioned oval funnel and two sets of kingposts, one forward and one aft, which serviced the four cargo holds via associated booms. The open promenades and ‘stepped’ lifeboats on each flank helped to lessen the superstructure‘s dominance, with the majority (seven) stationed on Sun Deck but individual one’s on A and B deck exaggerating the tiered aft deck arrangement. The bold yellow, green and white funnel livery, yellow cargo gear and mid-grey coloured hull helped to provide a distinctive, fresh and harmonious overall appearance.

The extensive use of aluminium (some 150 tons) allowed for very spacious interiors, particularly in First Class. On Vera Cruz accommodation was provided for 1,242 passengers, 198 first, 200 second and 844 third class in cabins and dormitories. Santa Maria’s complement and configuration was slightly different, totalling 1,296. They were looked after by a crew of around 300. Facilities were arranged over eight passenger decks, from the lofty and self-explanatory Boat and Sun Decks, down to emigrant dormitories in the bowels on F deck.

Boat deck primarily comprised the bridge, officers accommodation and radio and communications rooms, although there was a First Class games area aft of the funnel. Sun Deck had further crew space forward then the First Class and Second (also referred to as ‘Cabin’) Class children’s rooms, the gymnasium and First Class outdoor pool and lido furthest aft. A deck introduced the general alignment of First Class accommodation and public rooms forward with Second Class aft. The smoking room furthest forward and main lounge for the top tier passengers was then reversed for Second Class heading aft, with their smoking room overlooking a Lido, associated pool and the ship’s wake. The reading and card rooms occupied the central area between class divisions.

B deck was entirely devoted to First Class cabins, all of which had their own bathroom facilities. Luxury suites were situated furthest forward, the largest of which enjoyed ’double aspect’ illumination from forward and side windows. A Chapel was sited centrally on this deck, adjacent to the forward stairwell which linked all First Class areas. C Deck was primarily occupied by Second Class cabins although some First Class ones were sited forward of their embarkation lobby. The hospital and Third (later also referred to as Tourist) Class smoking room and adjacent outdoor deck space were aft. D deck included the First and Second Class restaurants, forward and amidships respectively, with Third Class cabins aft. The Second and Third Class embarkation lobby was situated on this deck. The only passenger spaces on E and F deck were more Third Class cabins and dormitories, together with the Third class restaurant centrally placed on E deck.

The ships’ interiors, particularly First Class, were notable for their richness and opulence being primarily the work of Henri Boulanger and Andrade Barreto with the input of many Portuguese artists. There was extensive use of exotic woods sourced from Portugal’s overseas territories and a conservative overall approach. The Santa Maria’s First Class lounge was a mix of red and gold hues, with large rectangular ceiling panels incorporating recessed lighting, a distinctive compass shaped circular wood inlaid dance floor and a large mural on the rear wall. Meanwhile the two deck high First Class restaurant included an elegant horseshoe shaped staircase, green walls and a lofty triptych of foliage panels. Combining tropical woods and high quality fabrics made for a luxuriant atmosphere.

As they steamed south from Lisbon passengers settled into the predictable rhythms of shipboard life. Although the crew, passenger complement and language gave the ships a distinctly Portuguese flavour, the entertainment on offer and daily rituals followed an almost universal pattern for the era. The ships’ tropical itineraries (whether on the La Plata or later Central America route) naturally focused daytime activities outdoors, focused in First and Second Class around the lido and swimming pools. As well as a dip the more active were catered for by the usual array of deck games or for the really keen the well equipped adjacent gym.

For many of course sunbathing on one of the padded steamer chairs, wrapped up with a good book (either outdoors or in the dedicated reading room) or a good chat whiled away many minutes, hours and eventually days at sea. Without the usual schedules to adhere to, food, in its many forms, became as much a time piece as a source of sustenance. Breakfast in bed or the restaurant would be followed by mid-morning bullion, lunch on deck or back in the dining room, topped up by the quintessentially English afternoon tea and then the culinary highpoint, dinner. For those with the space and stamina the midnight buffet offered a fitting finale to the day.

A company brochure ably, if overly romantically espouses the quaintly simple variety of distractions on offer each evening. Under the heading ’You name your pleasure’ it continues ’And when the moon rises over an indigo sea………In the lounges there is gaiety and laughter, as you dance to the rhythmic melodies of the ship’s orchestra…converse with friends….and make new ones. If a game of bridge intrigues you, you’re sure to find one going on in the smoking room. Or perhaps you’d prefer a moonlit stroll on deck for an unforgettable moment of watching a star-strewn sky…….’ Although there wasn’t a dedicated cinema/theatre, films were regularly screened in the ships’ lounges.

Utilising the steam of six boilers and powered by two sets of Parsons geared turbines generating 22,000shp, Vera Cruz and Santa Maria plied the ’Gold and Silver’ route between the Portuguese and Argentine capitals at a service speed of 20 knots, although they were capable of a maximum of 22 knots when required.

The ships’ time on the Lisbon-Buenos Aires service was short lived. In the face of fierce competition from Italian, Spanish and North European rivals they were shifted to a new Central and North America service in July 1956, terminating in Port Everglades (advertised as Miami), with outbound calls at Vigo, Funchal, Tenerife, La Guaira, Curaçao and Havana, returning via Tenerife, Funchal and Vigo. Advertised as ‘Sunshine All The Way’, marketing material predictably focused on the climate, ‘With sunshine and smiles, the happiest way to Europe’. Amongst the predictable hyperbole passengers were welcomed ’aboard your personal floating Palace’. Santa Maria would stay on this service for the majority of her career but her older sister was more nomadic. In 1958 Vera Cruz trialled a ’Circular Voyage’, sailing south from Lisbon, to Santos and Rio de Janeiro with interim calls at Funchal, Tenerife and St Vincent, then arcing up along the Brazilian coast to Salvador and Recife. The ship continued north, calling at La Guaira and Curaçao (the Venezuelan migrant trade was particularly important), before returning home via Tenerife and Madeira. Soon however she would be diverted to a wholly different service, exchanging tourists and emigrants for soldiers and bureaucrats.

Like most European colonial powers Portugal was in a state of transition, the Second World War had brought fresh impetus to independence movements across the globe. The momentum for change grew throughout the 1950s, culminating in a number of flashpoints at the turn of the 1960s. These incidents were given further significance by the broader geo-political struggles between capitalist and communist ideology. Like many others, Portugal’s African dependency of Angola was caught in this complex maelstrom.

Although theoretically no longer a colony (since 1951 Angola was assigned a special status of Portuguese Overseas Territory), this was largely a matter of semantics. Since 1955 it had been governed as a province of the mother country, under the control of Prime Minister António de Oliveira Salazar’s government. Relying on a projection of strength to rule firmly at home Salazar had little intention of releasing control of the African territories easily. When insurrections from neighbouring Congo challenged Portuguese authority the government ordered reinforcements.

Vera Cruz had already been switched to CCN.‘s Luanda liner service from 1960, the voyages included some troop movements. The following year, with the onset of full scale civil war in Angola, she was refitted primarily for carrying soldiers and their equipment. The long, drawn out nature of the country’s fight for independence, a central battleground in the broader Western and Soviet Cold War conflict, meant Vera Cruz spent the rest of her career sailing between Lisbon and West Africa. She was already one of a myriad of largely unsung workhorses, medium sized liners which plied their trade with little fuss or ceremony. Other than passengers, crew and soldiers, whose memories of passage on Vera Cruz remained etched forever, she is largely unknown by the wider public. Santa Maria would almost certainly have lived out her career in similar anonymity had it not been for the events of January 1961.

Henrique Galvão was an interesting and controversial character, a naval captain who gained prominence in the 1940s as the Angolan deputy to the Portuguese National Assembly. Formerly a supporter of Salazar’s administration he now criticised their tolerance of exploitive landowners and the forced labour practices employed in the colony. He was a prolific writer on a broad range of themes, primarily relating to his time in Africa, from politics to fauna and flora. Perhaps inevitably he became progressively marginalised at home and was imprisoned in 1952 for his outspoken views. He was also forced to retire from the military. In 1959, at the age of sixty four he escaped from Portugal (feigning illness he simply walked out of hospital dressed as a doctor) and took refuge, first in Argentina and later Venezuela. It was in Caracas that he devised Operation Dulcinea, (‘sweetheart’ in English) named after the peasant girl who Don Quixote imagines to be a beautiful woman. Like Miguel de Cervantes’ eponymous hero Galvão now embarked on his own deluded quest as part of a broader strategy devised by Directorio Revolucionario Ibérico de Liberación (DRIL) to undermine the Iberian leaders, Franco and Salazar.

The key woman in Galvão’s plan wasn’t a peasant but a radio operator, whose position enabled her to understand all the Santa Maria’s communication devices and monitor the deployment of officers of the watch. With Captain Mário Simões Maia in command the Santa Maria had embarked on one of her routine transatlantic voyages in the middle of January 1961. As usual many Spanish and Portuguese emigrants had left at La Guairá (Venezuela), where another small complement of passengers embarked. Amongst them were Henrique Galvão and the majority of his accomplices, hiding weapons in secret compartments within their luggage. The balance of the twenty four strong militants joined at Curaçao, mingling with approximately six hundred ’normal’ passengers.

At 0130 on the morning of 23rd January Galvão and his men made their move. It would take ten minutes to secure the ship and in particular the bridge where Santa Maria’s officers offered brave, if futile resistance. Given their superior numbers and firepower the hijackers inevitably prevailed, but officer of the watch Nascimento Costa was tragically killed in the ensuing struggle and another officer wounded. Passengers and crew, rudely awakened by the PA system, convened in the ship’s First Class lounge where Galvão addressed them and explained the situation in Spanish and Portuguese. Highlighting the ringleader’s rather flamboyant style the meeting concluded with Tchaikovsky’s 1812 overture echoing through the ship.

Captain Maia was initially ordered to make for St. Lucia where a lifeboat was launched containing Costa’s body, the injured officer, a nurse and a detachment of crew to row them ashore. The lifeboat had barely been released before Galvão instructed the Master to make for the Atlantic. The hijacking was an unprecedented event and the initial international response perhaps inevitably disjointed. The Portuguese reacted immediately but having been seized in international waters the appropriate legal position regarding other nation’s involvement was not straightforward.

It was soon evident why Galvão had selected his onboard accomplice. All external communication was initially cut-off, enabling the ship to sail undetected into the Atlantic, heading east towards the West African coast. Meanwhile an air and sea search had commenced, led by the United States and Dutch Navies whose nationals, along with Portuguese and Venezuelans made up the passenger complement being held hostage onboard the liner. A British frigate reportedly spotted the ship but subsequently lost contact. Once in mid-ocean Galvão started a series of communiqués to ‘Democratic newspapers and radio stations of the free world‘. As a natural linguist and experienced politician he eloquently and rather poetically set out the rebels position and demands, highlighting the alleged oppression and illegitimacy of Salazar’s Portuguese leadership and that of his counterpart, General Franco in Spain.

After nine days evading her pursuers Santa Maria was finally tracked down off the Brazilian coast, approximately 50 miles from Recife. The first sighting appears to have been by a Danish freighter. Thereafter a US Navy ’Hurricane Hunter’ maritime patrol aircraft relayed the liner’s position to a Task Force under the command of Rear Admiral Allen E. Smith. The US Navy closed in on her. A media scrum ensued as reporters descended on the Brazilian city and resorted to desperate methods for a possible ’scoop’. One French photographer parachuted into the sea and had to be rescued by a US Navy launch. With two US Navy destroyers encircling her Santa Maria hove to on 1st February and the American commander crossed by launch from his flagship USS Gearing, to negotiate with Galvão.

Dressed overall at Galvão’s insistence and with an accompanying naval escort, Santa Maria entered the port of Recife on 2nd February 1961. There was a confused, celebratory air onboard, with some passengers singing and dancing whilst a number of crew members were reported to have accosted their captors. The Santa Maria finally docked allowing Brazilian officials and medical personnel onboard and ultimately passengers ashore. A fleet of buses and ambulances awaited them on the quayside for although they had been fed and watered, food had been rationed and those in Third Class had been confined in squalid conditions, without access to fresh air, for the duration. Galvão was in high spirits as he disembarked and spoke to the world’s media.

Rear Admiral Smith labelled the twenty four, generally aged and motley conspirators ‘pirates’ but in the international media they were designated rebels, militants or terrorists. Whatever merits their cause might have had there was no escaping that an innocent ship’s officer had been killed, another seriously injured and civilian passengers and crew had been held against their will. Galvão found a sympathetic ear in the recently appointed Brazilian president Jânio da Silva Quadros and in exchange for releasing the passengers and crew, he and his fellow rebels were granted political asylum. Galvão‘s original goal and motives remain a mystery, although he later confided that the ‘rebels’ intended to land at Fernando Po, an island off Spanish Guinea, from where they proposed to launch attacks against Angola. The more immediate aim was bringing the world’s attention to Salazar and Franco’s authoritarian rule on the Iberian peninsular.

The Santa Maria was restored to her owners in Recife and sailed without passengers for Lisbon later in the month. Having been re-acquainted with the lifeboat that was jettisoned at St. Lucia she re-entered service, sailing the same Central America itinerary.

Except for that moment in the world’s spotlight the rest of Santa Maria’s career passed largely uneventfully. Like most liners her popularity waned with the aeroplane’s ascendancy and by the turn of the 1970s jets and jumbos were the transport of choice for the vast majority, no longer exclusively for the rich. There seems to have been little consideration given to converting either ship for a cruising role.

Vera Cruz remained on her West Africa service until January 1972 when she was laid up at Lisbon. She remained tethered for more than a year before being sold to scrap merchants in the Republic of China. On 4th March 1973 almost exactly twenty one years after her glorious maiden arrival, she raised steam and sailed from Lisbon for the killing fields of Kaohsiung. That same year, after developing problems with her turbine machinery, Santa Maria was withdrawn from service. The expensive repair work could not be justified but after a temporary fix she sailed for Angola and Mozambique on a freighter only one-way voyage. At Lourenço Marques she discharged the last of her cargo and then changed roles again, this time as a temporary tug towing two company freighters to be scrapped in Mauritius. From Mauritius she continued to head east and was beached alongside her sister on 19th July 1973.

Comments

Sorry, comments are closed for this item