In the annals of ocean liner history nothing can be considered more quintessentially French than Compagnie Generale Transatlantique (CGT), the French Line. Similarly no individual ship better represents that nation than Normandie, arguably the greatest transatlantic liner of them all. Nevertheless the inconvenient truth for those espousing the Gallic credentials of both the shipping line and liner is that CGT was formed by Portuguese immigrants, Isaac and Eugenie Péreire, and their most famous hull was designed by a Russian émigré, Vladimir Ivanovich Yourkevitch.

Yourkevitch was born in Moscow on 5th June 1885. Whilst still young his father, a schoolteacher, moved the family to the Tsarist capital St Petersburg, where in 1903 young Vladimir attended the local Polytechnic Institute. In 1907 he entered the Kronstadt Naval School, graduating as a shipbuilding engineer and attaining the rank of second lieutenant in the Imperial Russian Navy. On completion of all his studies he was assigned to the design office of the Navy’s Baltic Shipyard. The Russian Navy had been decimated by the more modern Japanese fleet during the Russo-Japanese war, most notably at the Battle of Tsushima on 27/28th May 1905. Yourkevitch and his colleagues at the Baltic yard were tasked with rebuilding the Imperial fleet explicitly to avoid such a humiliation in future. Conventional warship design at the time was based on the British battle cruiser Dreadnought, a ship so revolutionary when introduced in 1905 that it rendered all rivals obsolete, creating a template on which most nations would model their navies.

Yourkevitch however had his own ideas. He proposed a hull configuration radically different from any seen before. His design incorporated a very slender ‘knife-edge’ bow with a gentle flare rising to a raked clipper style peak. To compensate for the narrow bow and provide the requisite buoyancy the broad mid-ship area incorporated exaggerated tumblehome, the notable sagging which extended below the waterline. Tank tests at the Navy’s Konstadt facility proved the merits of the young cadet’s design, providing superior sea keeping qualities and fuel efficiency compared to its rivals. The unique hull form first manifested itself in the first Russian dreadnought Sevastapol, and was later adopted for a new breed of Borodino class ‘super-dreadnoughts’. In the meantime Vladimir Ivanovich was transferred to a new department, tasked with overseeing the design and construction of the Imperial Navy’s fledgling submarine fleet.

The October Revolution of 1917 put paid to the four super-dreadnoughts and ultimately Yourkevitch’s life in his native land. He became an officer in the ‘White’ Russian army but defeat at the hands of communist forces in the Crimea in 1920 saw him fleeing to Turkey and taking refuge in Constantin-ople. Such a sudden transformation in fortune may have broken a weaker man but the ever resourceful Yourkevitch worked first as a stevedore and then a car mechanic. Ever restless he moved to Paris with his second wife, Olga Krestovskaya (his first tempestuous marriage whilst still a young man in Russia had ended in divorce) and secured employment as a turner at local Renault manufacturing plant. Olga was in many ways the galvanising force of that relationship, seeing her husband’s talents going to waste, she encouraged and cajoled him into applying for maritime architect jobs. Ultimately he successfully obtained work as a draughtsman at the Chantiers d’Atlantique shipyard offices at Penhoët near St. Nazaire. The timing could not have been better.

The French line, France’s principle transatlantic carrier was seeking tenders for a new liner, nick-named the ‘Super Ile de France’ with reference to her famed predecessor. The intention was to build a huge, luxuriously appointed ship capable of wrestling the Blue Riband for the fastest crossing but also to eclipse Germany’s Bremen and Europa, Italy’s Rex and Conte di Savoia, White Star’s prospective new Oceanic and Cunard’s, as yet unnamed, superliner project. Yourkevitch worked through many nights, adapting his Russian battle cruiser designs for the hull of the new vessel. Showing his customary resilience, Vladimir ignored the initial rejection of his ideas (it is alleged that he also approached Cunard/John Browns shipyard with the design, with a similarly negative response), ultimately receiving the support of a fellow Russian émigré, Admiral Poguliev of the French Navy. With such an endorsement, Penhoët management felt obliged to consider Yourkevitch’s submission. His drawings were reviewed by the managing director André Lévy, who recommended a model be made and tested at the company’s Versailles facility. In the end the full tank tests were undertaken in Hamburg, where the model performed exceptionally well, supporting Yourkevitch’s assertion that his design could attain the same speed as conventional hulls whilst using almost 20% less power. After further scrutiny and appraisals back in France, Yourkevitch’s hull was formally adopted for the new liner in 1929. Designated at the time by its builders reference T6, she would ultimately become Normandie. Certainly it was a bold step by the company, given his relative inexperience and how prestigious the commission was, nevertheless the data from the tests was irrefutable evidence of his design’s superiority.

It did however cause a certain amount of political consternation. As a (quite literally) ‘flagship’ national project, the French were rather reluctant to acknowledge the significant role of foreign individuals and companies in the design and construction. Yourkevitch was only mentioned in the context of being ‘one of the team’ until Olga, with typical ebullience, asked a patient, who happened to be a newspaper editor, to run the full story of her husband’s central role. For his part Vladimir Yourkevitch would remain publicly and privately unstintingly grateful to Chantiers de L’Atlantique’s senior management for accepting his design. He continued to work on new projects at Penhoët after Normandie’s completion, including the hull configuration for a prestigious new flagship for Compagnie Sud Atlantique’s Bordeaux to Buenos Aires service, which ultimately emerged as Pasteur. However by the time this vessel was completed the Russian and his young family had migrated once more. In 1937 Vladimir, Olga and their young son George moved to the USA and settled in New York. Inevitably they crossed onboard the Normandie.

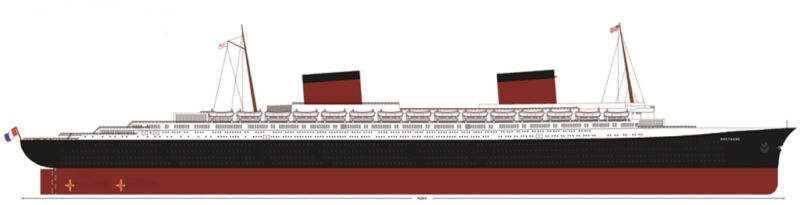

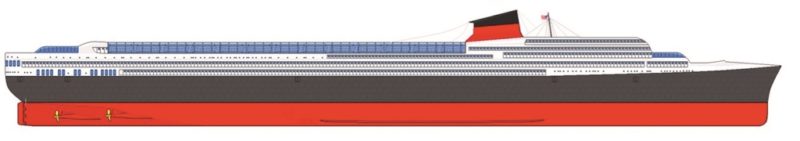

Having established offices in Manhattan Yourkevitch now devoted himself almost exclusively to a new project that was not only technically but also socially amongst the most radical ever conceived. In October 1938 the French Line announced that they were seeking a running mate for Normandie, to compete directly with Cunard’s two ship weekly transatlantic service. At Penhoët the Normandie blue prints were dusted off. Like their British counterparts it was envisaged that the new vessel, to be called Bretagne, would be an updated version of her predecessor, the most visible difference being a twin rather than triple stack configuration. Meanwhile, however, over in Manhattan, Vladimir Yourkevitch was finalising plans for a ship unlike any that had preceded it. With a length of 1,148 feet and breadth of 138 feet, his vessel, estimated to be well in excess of 100,000 grt would be by some margin the largest in the world. If the dimensions were exceptional it was the profile of Yourkevitch’s design that was even more extraordinary. Whilst the hull resembled Normandie’s, apart from a spoon stern, the forward superstructure and bridge were topped by a pair of tapered, athwart ship stacks. In the absence of masts these funnels, located at the extremities of the superstructure would support all wires, lights and flag.

Set far forward, the funnels and the supporting superstructure ended abruptly where a serried row of lifeboats began. These were positioned above a two deck high, full width superstructure extending almost to the stern. The overall streamlined concept was taken even further by enclosing the whole boat deck in retractable glass screening. Distinctive or downright ugly according to one’s perspective, Yourkevitch’s Bretagne was based on a whole new concept in transatlantic travel. He was undoubtedly a visionary, seeing as early as the 1930s the ultimate hegemony of air travel, his Bretagne would steal a march on the airlines by providing spacious, clean but also cheap accommodation for 5,000 passengers in a single, egalitarian class. Catering primarily for American vacationers the basic fare broadly undercut tourist class on competitors. However this did not include food. In a further radical departure from convention Yourkevitch proposed a range of eating options from self-service cafeterias to Haute Cuisine restaurants, allowing passengers to dine according to their preference and budget. With such a huge vessel it was also possible to provide a broad range of leisure facilities including swimming pools and sports courts but also redirecting the focus away from large public lounges and more specialist intimate venues. In essence Yourkevitch’s concept bore a closer resemblance to 21st century cruise ships than contemporary liner tonnage. In one respect however, his Bretagne was clearly a transatlantic carrier. Yourkevitch predicted an unprecedented 34 knot service speed, utilising powerful engines coupled with the streamlined features previously mentioned.

Although the French Line seriously considered his proposal, various factors resulted in the adoption of the modified Normandie design for their new ship. Although the Russian émigré insisted his design would be cheaper to build (a fact disputed by the French Line president) the Normandie blue prints already existed. With the loss of their liner Paris to fire at Le Havre in early 1939, it was necessary to expedite construction of the new vessel. Perhaps most significantly no slipway or dry dock in France could then accommodate a ship on the scale that Yourkevitch envisaged. Of course, Bretagne would never actually materialise. The building slip at St. Nazaire was needed for warship construction and after the fall of France in June 1940, all prospects of a new French flagship evaporated. Ironically Yourkevitch’s design included provision for rapid conversion into a 16,000 capacity troopship. In his mind the radical Bretagne concept never died and in the post-war era those plans were revived with an even more radical single offset funnel design.

If the Bretagne occupied Vladimir Yourkevitch ‘s professional time following this move to the United States that would change dramatically once his newly adopted country entered the war. The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour in December 1941 provoked an immediate response from the previously neutral Americans. Urgency was the watchword that dominated the agenda, retribution the goal. Normandie was requisitioned, and renamed USS Lafayette. In the two long years of idleness at Pier 88, the French skeleton crew had maintained her well but in the newly infused atmosphere speed was everything. In their haste to dismantle the greatest ocean liner of all time and transform her into one of the largest and fastest troopships of the era, safety was compromised. Cold and often wet, enduring long hours in poor light, shipyard workers strived to complete the commission within impossibly tight, ever changing deadlines. The complex logistical difficulties of safely replacing Normandie’s exquisite interior with Lafayette’s utilitarian fittings was exaggerated by the location. The ship was too large to use the facilities at the local Navy Yard and so remained tethered to her berth at Pier 88.

The ninth of February 1942 dawned bright but bone-numbingly cold. As Rosins Dry Dock & Repair Co. personnel trudged up the gangways (still bearing their flamboyant French Line markings) their workplace loomed out of the ice encrusted waters of the Hudson. Amongst the numerous tasks on the day’s itinerary was the removal of four pillars once supporting elegant Lalique light fixtures, in what had been Normandie’s Grand Salon but in the utilitarian name of war was now dispassionately entitled part of the Main Troop Recreation Compartment.

At 2.37 pm as Clement Derrick’s oxyacetylene torch sliced through the final leg of the fourth pillar, the protective asbestos shield in front was withdrawn, momentarily too early. The cascading arc of sparks fell onto one of numerous batches of kapok-filled life jackets, awaiting despatch to the sleeping quarters below. Wrapped in tarred cloth the bundle ignited instantly, life preservers transformed into life destroyers. Initial attempts to tackle the fire were comically tragic. Those in the immediate vicinity tried unsuccessfully to stamp it out or throw the burning bundles away which only spread the flames. In a scene of slapstick stupidity, a workman carrying pails tripped and spilt the water short of its target.

So the fire spread, fanned by the chill wind blowing from the New Jersey shoreline. Plumes of acrid black smoke engulfed the ship and billowed inland.

At his offices Vladimir Yourkevitch heard the multitude of sirens as fire appliances raced through the Manhattan streets and smoke enveloped the city. Perhaps he sensed what had happened, that inexplicable knowing that goes beyond rational judgement. Whatever the reason, he headed out, joining the ever increasing inquisitive mob on a trek to the shoreline, where West Forty-eighth Street tumbled into the North River.

There his worst fears were confirmed. USS Lafayette, his Normandie, was a chaotic smoke-sheathed inferno. As firemen bravely mounted the gangways, battling the outflowing tired of choking, shocked and smoke smudged shipyard and naval personnel, he pleaded with the supervising officer to let him onboard. He could find the main sea cocks, open them and allow the great ship to settle in an upright position. In truth with the fire already rampant, power and therefore lighting disabled, the little Russian’s plan was probably doomed to failure. In any case Yourkevitch was refused entry, held back along with 30,000 other inquisitive New Yorkers at 11th Avenue.

None appeared willing or capable of taking control to assume responsibility for managing the evacuation or attempts to save the ship. As the disaster unfolded, senior naval officers obsequiously demurred to each other, leaving only the fire department to make decisions and take meaningful action. Unsurprisingly their sole goal was containment, if Lafayette’s conflagration caught hold of Pier 88 and spread, the consequences could be catastrophic. So, hour after hour the fireboats nudged along her port flank and shore-side appliances dowsed the flames. The ‘safe’ sixteen degree list became more pronounced. It was low tide and Lafayette’s apparent stability was mere illusion, she was resting on a rock ledge, a residual shelf from when Pier 88 was extended into the Manahattan shoreline to accommodate her vast length. Under the incessant deluge almost seven thousand tons of icy Hudson water accumulated on the upper decks, trapped where molten metals had blocked scuppers and outflow pipes. As the tide turned and then drifted in, the great ship rose, tilted and ultimately, under cover of darkness, capsized.

Comparisons with a beached whale are inevitable. This great sea creature, so balanced, svelte and beautiful on the ocean, lay grotesque and impotent on her side between Piers 88 and 90. Whilst naval experts, architects including William Francis Gibbs, enthusiastic amateurs and self-serving politicians pondered what to do with that hulk, Yourkevitch dedicated himself to resurrecting his ship. He drew up multiple plans including, ultimately transforming her into a foreshortened, mid-size emigrant carrier. Alas like his plea to be allowed onboard that frigid February day in 1941, they fell on deaf ears as the American naval establishment circled their wagons. After two long years, devoid of funnels, mast, superstructure and dignity, Lafayette emerged from the Hudson mud and was towed out of sight. In September 1945 and despite Vladimir Yourkevitch’s last ditch attempts the US Maritime Commission sold what was left for scrap to Lipsett Inc. With the new owner’s name emblazoned on her flanks, she was towed to Port Newark, where the final skeletal element of what had once been Normandie was craned ashore for smelting on 6th October 1947. Yourkevitch’s frustration at not being allowed on board in 1941 was eclipsed by the Maritime Commissions obstinacy in rejecting every scheme he devised to revive her. Their decision may well have been fostered by embarrassment at the whole sorry tale of Normandie’s loss but it hurt him deeply.

As previously mentioned in the post-war era, Yourkevitch reappraised his Bretagne drawings, the concept’s time seemed to have arrived even the French Line remained ambivalent. With its single off-set funnel this new incarnation appeared even more quirky than the original. The French could not afford such a grandiose project and instead insisted on revamping the Ile de France and rebuilding the pre-war Europa which had been awarded as scant recompense for the loss of Normandie.

Even as a septuagenarian, Yourkevitch worked on new developments. In 1956, he was brought in as a consultant by Hyman Cantor to assist in plans for a pair of gargantuan liners of over 100,000 tons and 1,100 feet, designed to carry around 9,000 passengers in an arrangement broadly similar to the original Bretagne. Peace and Goodwill were basically floating hotels conceived by a hotelier and Yourkevitch is said to have become disaffected by some of the compromises this required.

Ultimately the Sea Coach Line project foundered on financial grounds by which time (in the early 1960s) Vladimir Ivanovich was finally reducing his work commitments. Yourkevitch died on 16th December 1964 and was buried, according to his wishes, in the Russian Orthodox cemetery at Nova Diveevo, New York. Three nations sought to ‘own’ his legacy, the Soviet Union referring to his birthplace, financial and vocal support for the Soviet cause in ‘The Great Patriotic War’ (World War II) and his Orthodox faith. The French belatedly lauded his role in creating Normandie, their national icon and the United States promoted his choice to move there in the 1930s and stay for thirty years. In truth probably none of them were correct. The testimony of those who knew him best indicate that irrespective of where he lived, the pervading political winds or who he worked for, at heart he was and remained a simple Russian.

Above: The revised plans of the innovative vessel that was never built.

Comments

Sorry, comments are closed for this item