The Designer of the ‘Big U’

Of all the great ship designers, perhaps none is more inextricably linked to a single, exceptional vessel, than William Francis Gibbs and the SS United States. Yet to focus entirely on this culminating achievement, this manifestation of his ‘big ship’ ideal, is to miss out on the life of an extraordinary and complex man.

Gibbs was born on 24th August 1886, the son of a dogmatic financier whose skill at accumulating multi-million-dollar fortunes was matched only by his ability to squander them. Young William attended Delaney School in Philadelphia, before moving on to Harvard in 1906, as society and his parents dictated. Following three years of study, but notably without a degree, he moved to New York, where he studied law, ultimately graduating from Columbia law school in 1913. Superficially, Gibbs was fulfilling his father’s expectations, settling into a ‘worthwhile’ life as a real estate lawyer in his native Philadelphia. Secretly however, William Francis and his younger brother Frederic Herbert were pursuing a parallel course. Gibbs’ studies and day job masked a secretive nocturnal and weekend obsession. In the dead of night, he was studying naval architecture.

The Gibbs brothers would later pinpoint their nautical epiphany to 12th November 1895, when as youngsters they gazed awestruck as the 11,629grt America Line’s St Louis was launched from Philadelphia’s William Cramp and Sons shipyard into the Delaware River. Although the impact of this event on such impressionable boys cannot be underestimated, Gibbs had in fact been drawing ships from a much more tender age. Each summer the family decamped to Spring Lake New Jersey, from where the brothers scanned the entry channel to New York, assessing and re-evaluating the design of the vessels steaming past.

By 1914 that childhood hobby had morphed into adult obsession. The following year, coincidentally the same month that Lusitania was torpedoed off the Irish coast (May 1915), William Francis Gibbs gave up the legal profession entirely and devoted himself full-time to ship design, more specifically what he referred to as ‘the big ship’ project. Gibbs was already fascinated with the pursuit of speed, probably influenced by a trip to Europe in 1907, when he sailed out on the then new, ill-fated Lusitania and returned on her sister, Mauretania. Although neither of the brothers achieved a recognised qualification in their chosen vocation, William and Frederic developed detailed blueprints for a pair of 1,000 ft. four-funnelled liners capable of over 30 knots. These were the first, formative ‘big ship’ plans. Commonly referred to as the Boston and Baltimore, these vessels superficially resembled the German speed queens of that Edwardian era, with their long, low profiles and paired stacks. However, in addition to their unusual dimensions, their external profile hid a revolutionary power plant. The Gibbs brothers proposed achieving the ships’ exceptional pace utilising the first application of electric-drive engines in a transatlantic liner. To this end they approached the General Electric Company.

Not content with simply designing the ships, Frederic also proposed new termini for the service. By relocating to a bespoke western port facility at Fort Pond Bay, Long Island, and another at Brest on Brittany’s Finisterre peninsular, the brothers estimated they could shave four hours off a transatlantic crossing. They considered and calibrated every aspect of the ships and their shore facilities, traits that would manifest time and time again in future projects. With admirable bravado, backed by earnest endeavour and their homespun technical ability, ‘Willie and Freddie’ took their detailed plans to the office of Ralph Peters, chairman of the Long Island Railroad, part of the vast Pennsylvania Railroad organisation. Unannounced, the two lanky brothers caught Peters’ attention sufficiently for him to contact J. Piermont Morgan Jnr., supremo of the International Mercantile Marine (IMM), which controlled virtually all transatlantic shipping lines of the era. Morgan was so impressed that he arranged for the Gibbs brothers to be put on the IMM payroll and they moved into offices on Broadway to work up their designs. An approach to US Naval hierarchy was similarly well received. Not only had the brothers proven their technical ability, but they had also, probably even more significantly, become increasingly adept at manoeuvring around the complexities of big business and Washington’s political and bureaucratic establishment. This synthesis of commercial and military interest would inform many subsequent projects, most notably the SS United States.

When the United States entered the war, William Francis dutifully served on the Shipping Control Committee. When the conflict reached its conclusion he attended the Versailles Peace Treaty negotiations as assistant to Edward Hurley, Chairman of the US Shipping Board. Although still employed by the IMM (William and Frederic were appointed Chief and Assistant Chief of Construction respectively) the shipping world was in a state of flux. A new artist impression of ‘the big ship’ concept showed a vessel of similar dimensions to the original but with three broader stacks and a rounded forward superstructure and bridge. There were yet more military design features incorporated. Tank tests of the hull configuration would run for the next few years, supervised with meticulous detail by the elder Gibbs.

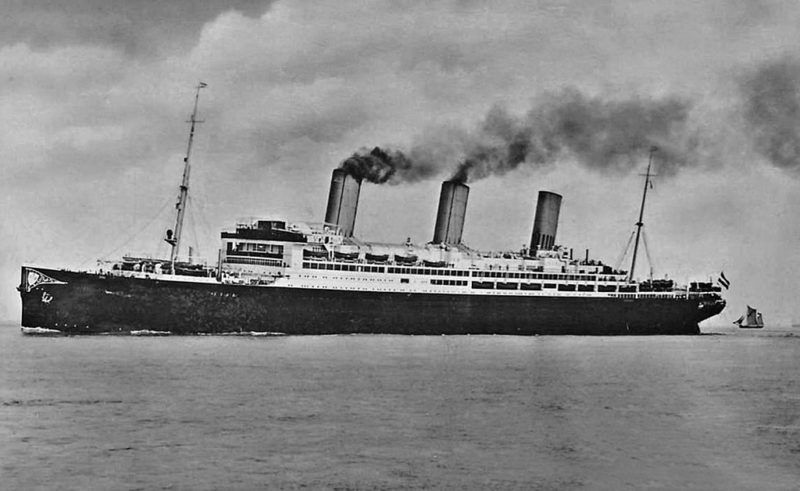

The Gibbs brothers’ stock had risen markedly during the conflict but ultimately a surfeit of new tonnage rendered their proposed liners superfluous. Nevertheless, the war’s aftermath also produced an opportunity. Remarkably, given their inexperience and lack of formal qualifications, the first major project the brothers secured was the conversion of one of the largest passenger ships afloat. The ship they were tasked with restoring to commercial service was the Leviathan, one of a trio of ‘monsters’ built for the Hamburg American Line’s Cuxhaven to Hoboken, New Jersey service. As Vaterland she had made just five transatlantic crossings before war broke out in August 1914. Caught at her New Jersey berth, she was laid up in safety. American neutrality seemed assured, indeed there was a strong pro-German sentiment in the country, however when the United States entered the war on the allied cause, Vaterland was rapidly requisitioned, stripped of her fixtures and fittings and pressed into trooping duties. She sailed in this role until shortly after the armistice and then resumed her lay-up status at Hoboken, awaiting her fate. With sister ships Imperator and the incomplete Bismarck assigned to Britain as replacements for war losses Lusitania and Britannic respectively, it was left to the US to formally adopt the remaining ship.

The Shipping Board were left in a quandary as to what to do with her. Like a maritime cuckoo, Leviathan was so much larger and faster than the rest of the American mercantile fleet that she simply didn’t fit in. The IMM’s America Line was the only obvious ‘nest’ and naturally this fitted neatly with the Gibbs brother’s conversion plans and position as employees. The dilemma seemed resolved, alas it would prove to be anything but.

Enter William Randolph Hearst, a newspaper mogul whose ‘yellow journalism’, a propensity for sensationalist, divisive and invariably scandalous stories was already changing the way in which ‘news’ was reported. Hearst’s papers started to run spurious stories regarding the IMM and its operation, especially the British Admiralty influence over the White Star Line. The papers inferred that in IMM hands the British might also have undue influence over any wartime deployment of the mighty ‘Levi’. Although totally unfounded some of the mud stuck and without the vocal support of the Shipping Board, Morgan’s IMM felt obliged to distance themselves from the Leviathan project.

William and Frederic Gibbs were now the ones left in a quandary. They were approached by the Shipping Board to take over the Leviathan project despite their employer’s (the IMM) exclusion. In a typically bold and confident move they accepted the commission and so in 1922 Gibbs Brothers Inc. was formed, with the fraternal division of labour neatly split. William Francis concentrated single-mindedly on ship design whilst younger brother Frederic managed the running of the office and company. The schism with IMM management, most notably the Franklin family, would endure for decades.

To begin the mammoth task of converting the Leviathan, William Francis Gibbs approached the liner’s builders, Blohm & Voss, for Vaterland’s original blueprints. In response he received a $1 million price tag, the shipyard was still smarting from its obligation to hand over the brand new Bismarck to become White Star line’s Majestic. Riled by what he perceived to be German extortion, Gibbs employed 100 draughtsmen to internally measure and document every inch of his new charge. Two months later, and at a cost of $300,000, Gibbs had his detailed plans, but also and significantly a thoroughly documented survey of Leviathan. Conversion from coal to oil fired boilers and provision of increased water storage capacity were the main engineering changes. Internally there was neither scope nor budget for radical structural transformation, Gibbs concentrated instead on restoring the pre-war décor with minor American accents. When the refurbishment was complete William Francis’ pre-occupation with speed manifested itself in a set of contrived sea trials. Utilising the Gulf Stream Leviathan attained 28 knots, superficially eclipsing the maximum speed of the Blue Riband holder, Mauretania.

Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of the whole affair was the Shipping Board’s decision to appoint Gibbs Bros Inc. as operators of the ship for its first six months in service. The company, supervised as ever by the remarkable Frederic, devised everything from menus to uniforms, hired and where necessary fired crewmembers, ordered victuals, fuel and machinery spares. It was a task without parallel but without flinching they achieved it. Following her maiden voyage, which departed on 4th July 1923, Leviathan became one of the most popular liners on the Atlantic, even whilst suffering from two major handicaps, the lack of a comparable running mate and prohibition. It may have been a protracted affair, but Leviathan’s refurbishment was considered an unprecedented success and Gibbs Brothers Inc. was established as the nation’s principal ship design specialists.

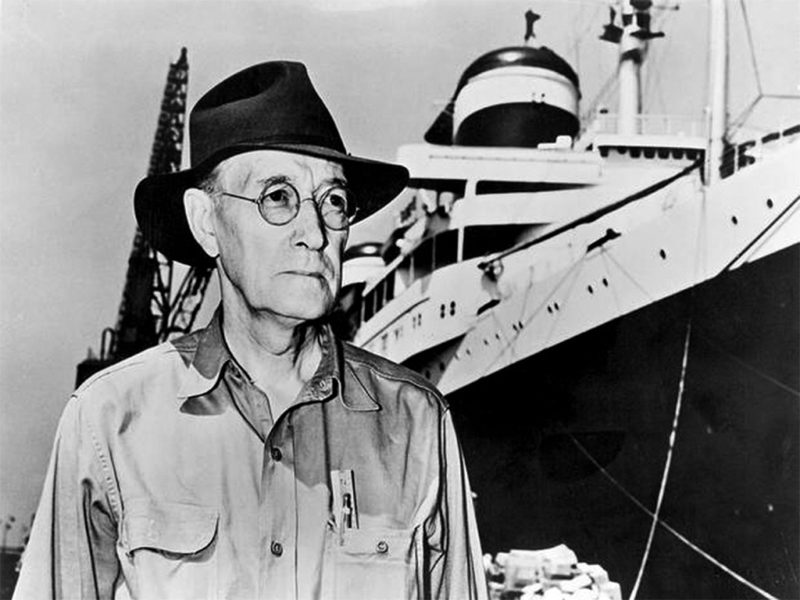

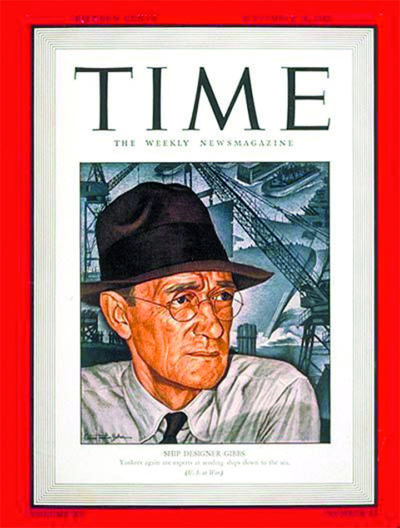

The Gibbs brothers were workaholics. Inseparable throughout, they even shared a house until William Francis fell for recently divorced Vera Cravatli Larkin in 1927. A whirlwind romance ensued and within a matter of weeks they were married. Gibbs senior could be an awkward, cantankerous, and imposing character. Tall and thin, sporting swept back thinning hair and learned circular metal spectacles, he invariably wore a black suit, starched white winged collar shirt and a black tie. Whether cultivated or not, there was something funereal about his entire disposition, at once haunted and haunting. Brusque to the point of rudeness, he loathed bureaucracy and displayed an inverted snobbery borne perhaps from deep-seated childhood experience. “If there is one thing I hate it’s big shots”, he once told a reporter, although the irony was he had become one. The air in his 21 West Street office was invariably blue with colourful language and he was an exacting and ruthless employer. Nevertheless, those who worked at Gibbs Bros. Inc. adored him and their loyalty was legendary. For William Francis ten-hour days were the norm and holidays an inconvenience. He would be up at 06:30 each day for a breakfast of weak, sweetened tea and biscuits. His wife would later comment that he only ever really ate one meal, dinner, presumably lunch would simply have been an impediment to work. He spent his days sitting on a stool at a drawing desk and somewhat bizarrely, given his obsessive secrecy, demanded verbatim notes be taken of every utterance he made, including the profanities. Every telephone call was recorded. Another, self-effacing quote, perhaps sums up his character perfectly, “beneath this rough exterior beats a heart of granite!”.

Despite the devotion to his chosen profession, Gibbs maintained a broad range of interests. As children the brothers were drawn to fire (a neighbour was in the local fire service), but rather than developing pyromaniac tendencies, they gravitated towards fire safety and prevention as their mantra, ultimately leading to the design of New York fire departments most powerful river-to-land based pumping equipment. Opera was another passion and William Francis Gibbs became renowned for his generous donations to the arts, although as a habitual early riser he rarely attended productions. He was also a deeply religious man and regular church goer. Nevertheless, work remained his driving force and the pursuit of his ultimate goal, the ‘big ship’, superseded everything else.

Gibbs Bros. Inc.’s first newbuild design from the keel up was the Malolo of 1925, for Matson Line’s Pacific service. It firmly cemented their burgeoning reputation. Built at the same William Cramp and Sons yard where the brothers had witnessed St Louis’ launch so many years before, Malolo would prove to be the fastest and safest Pacific liner, surviving a midships collision on trials that would have sunk most contemporaries. She was followed by three similarly large and well reputed Matson Liners, Mariposa, Lurline and Monterey. In Malolo’s wake the brothers, and from 1929 a new business associate, the already established and well-connected yacht designer Daniel Hargate Cox, also created a highly acclaimed quartet of vessels for Grace Line. Their portfolio of clients and designs continued to grow, incorporating everything from liners and millionaire yachts to landing craft and tugs. From 1933 the company created a new breed of fast and efficient destroyers for the US Navy. Nor was their output limited to the ships themselves, the company was constantly evolving new, more powerful boilers and associated machinery. Nevertheless, despite overseeing the whole complex operation in conjunction with his brother and their business partner, Gibbs senior never took his eye off his ‘big ship’.

A huge step towards that goal came in 1936, when Gibbs & Cox secured the design contract for the most prestigious passenger ship in the US merchant fleet. America was a fine vessel in her own right but also a form of prototype, not only in terms of design but also political standing. Crucially America provided the Gibbs brothers with influence in and over the newly formed US Maritime Commission. Launched on the eve of war, America was, at 33,532 grt and 723 feet long, Gibbs and Cox’s largest new liner commission to date and was completed in 1940. Despite the USA’s neutrality, United States Lines were unwilling to risk their new vessel on the run to Europe, so they sent her south on Caribbean cruises. With her black hull painted with prominent stars and stripes and neutrality wording, this ensued until June 1941, six months before Pearl Harbour, when she was assigned to the US Navy and sent to Newport News for preliminary conversion to troop ship USS West Point. Initially she sailed on repatriation duties with Germans and Italians displaced by the war, however once the USA joined the allied cause USS West Point became a full-time troop transport, plying all the world’s oceans. In February 1946, her military service ended, and she was returned to United States Lines at New York. Restored by her builders at Newport News, America made her maiden transatlantic crossing in November 1946, more than six years later than scheduled. In the immediate post-war era, America operated alone, the pre-war Washington and Manhattan had been driven hard during trooping duties and therefore joined the reserve fleet and undertook austerity sailings respectively.

Although during this period William Francis Gibbs was formulating further plans for his ‘big ship’ officially from 1943, the genesis can be traced back to the Boston/Baltimore concept of 1915, he was also instrumental in the US war effort, both from a design and a production perspective. Gibbs & Cox were, at the time, the most prolific ship design company on the planet, responsible for an astonishing 75 per cent of all US naval and merchant vessels produced during the war years. They also supervised the conversions of several liners into troopships, including Ile de France, Pasteur and ultimately Europa. However, Gibbs’ genius manifested most obviously in the standardisation of production, effectively transforming the shipbuilding process into a factory of which Henry Ford would have been proud. Rather than months or years, ships could now be completed in a matter of weeks or days. Liberty and Victory freighters together with their destroyer and corvette escorts were churned out at an astonishing rate. If Winston Churchill credited Cunard Queens with shortening the war in Europe by a full year, a similar accolade could be bestowed on William Francis and Frederic Herbert Gibbs. Their production methods, implemented in shipyards across the United States, created the ships to carry those troops’ arms and equipment. William Francis Gibbs’ influence was such that he also, reluctantly, found himself a member of the War Production Board. Although he abhorred the posturing that this entailed, the posting once again heightened the political influence that ultimately bore dividends.

Whereas the Great War thwarted his ambition, the Second World War undoubtedly helped Gibbs’ ‘big ship’ cause. Stung by the unprovoked attack on Pearl Harbour, the United States joined the allies in December 1941 and immediately sought a means of transporting GIs to carry the fight abroad. USS West Point, as America was now known, and a plethora of domestic and foreign liners circled the globe, transporting up to 8,000 troops at a time. Even more influential were the three ‘monsters’, as New York stevedores called them. Swiftly commandeered and renamed USS Lafayette, the first of the trio, Normandie, was to be consumed by fire and capsize at her Manhattan berth in February 1942. A victim of negligence, maladministration, and haste, her demise deprived the US Navy of their largest troop transport. As one of the most eminent members of the special committee appointed to oversee the subsequent salvage of Lafayette, Gibbs persistently argued that the hulk should be saved, repaired, and redeployed to help the war effort. The other two ‘monsters’, Cunard’s Queens, were meanwhile pressed into service carrying thousands of troops between all the major theatres of war. In the run up to D-Day, the US Government leased them to carry entire Divisions, up to 16,000 soldiers, across the Atlantic. As the conflict unfurled the Washington political establishment realised that if there was to be another conflict the United States would need its own vessels.

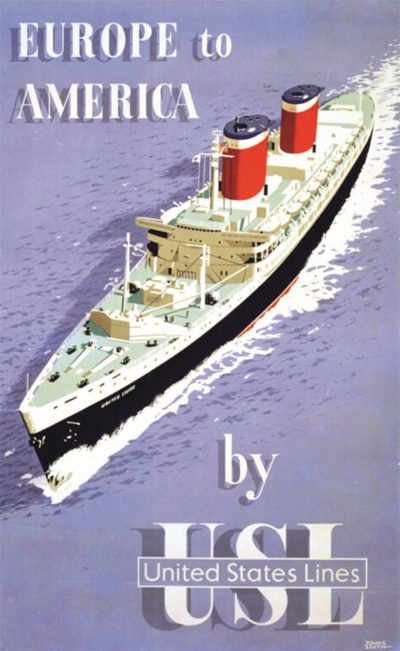

“We must have an outstanding ship the public can get behind, like a Cup defender. I want berths for two thousand passengers, accommodation of the same quality as America’s, not super, but very good, and the ability to make a round trip across the Atlantic every two weeks, like the Queens. It must gain the blessing of the Navy and the Maritime Administration by being quickly convertible to a transport. Efficiency and fuel consumption must be well in advance of anything known today!” Such were the exacting demands of the US lines’ John Franklin when he commissioned Gibbs & Cox to design a consort for the renovated America in 1946. It might have intimated lesser men but for William and Frederic Gibbs this was fate, simply the culmination of all the years of experience, realising that childhood vision. Although as previously mentioned detailed studies had commenced in 1943, William Francis Gibbs spent two further years compiling and refining plans. The two most significant drivers were to be speed and safety, particularly fire prevention, and the brothers’ wartime experience would be instrumental in fulfilling them.

Achieving the first component, speed, was essentially a simple formula, minimising the vessel’s weight whilst maximising available horsepower. It necessitated the most extensive use of aluminium alloy then incorporated within an ocean liner, utilising technologies that had been honed during the war years. Most superstructure decks and bulkheads, but also the funnels, masts, lifeboats and davits were manufactured using the alloy. Although similar in length and beam to the Cunard Queens, the new ship would only register two thirds of the British ships’ tonnage. To drive the American challenger at her 30 knot service speed, and the faster speeds demanded by the US Navy, her power plant essentially mirrored that of the new class of aircraft carriers, developing, it was revealed in the late 1960s when the information was declassified, an astonishing 240,000shp. By comparison, the ship widely regarded as ‘best of the rest’ in terms of speed, the French Line’s SS France of 1962, generated 160,000 shp. Safety and fire prevention were inevitable requirements of her envisaged trooping role but also a lifetime’s preoccupation for the designer. Gibbs’ obsessiveness persistently shines through. Whole mock-up cabins were torched in the Newport News warehouses to ensure no unseen combustible material had been included in error. The famous story goes that only the butchers block and piano were made of wood and even with the latter Gibbs only relented after heated exchanges with Theodore Steinway, who refused to build an aluminium facsimile. Ever since Titanic the word unsinkable had become anathema with reference to a passenger ship but United States was inarguably worthy of the adjective. She was designed to remain afloat even if four of her watertight compartments flooded and Gibbs distantly but consistently monitored the distribution of ballast etc, to ensure she was always as stable as possible which was one of the key reasons Malolo survived her collision. From a military perspective the other key element of the ship’s safety was the split engine configuration. Each autonomous chamber contained boilers, turbines and associated generators/ motors, thereby allowing power and propulsion to be maintained in the event of one being damaged or destroyed by, for instance, a torpedo strike.

A model of the new liner was revealed at Gibbs & Cox Inc.’s offices in 1948. Three yards tendered for the work, with Newport News Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Company winning the resultant contract, having stipulated the lowest price ($67.3 million) and earliest delivery date (1,128 days). The vessel was listed as Hull 488 by the builder but became more than a number in May 1949 when ‘United States’ was selected as the ship’s name.

In his capacity as Construction Supervisor, Gibbs dictated every element of the building process, infuriating the Newport News management and workforce with his micromanagement style and abrupt manner. Indeed, United States revealed the best and worst elements of Gibbs’ personality. Secrecy was sacrosanct. Although characterised as a demand from the US Navy given her intended military use, it was primarily driven by Gibbs’ manic jealousy. A staunch patriot he had been waiting almost half a century to eclipse the Europeans and he had no intention of allowing them to benefit from his knowledge and experience. Despite their frustration a strong mutual respect developed between designer and builder, which ensured that not only would United States be the epitome of fine craftsmanship but also details of her configuration and powerplant remained a self-contained mystery until revealed in 1968.

Many of the techniques employed to build the United States can be traced to Gibbs & Cox’s wartime experience. William Francis stipulated that construction should take place in a graving dry dock rather than on a conventional inclined building slip. In part this was to hide her top-secret underwater elements, but it also simplified the process and allowed her to be almost structurally complete when launch day arrived. The first keel plate, a prefabricated 55-ton section, was laid without ceremony on 8th February 1950. Prefabricated sections were quickly incorporated and soon the liner started to take shape. In addition to speed and safety, Gibbs other obsession was the size of his ‘big ship’s’ funnels, creating purportedly the largest (again out of aluminium) to ever adorn an Atlantic liner.

As construction progressed, events half a world away almost resulted in a change of purpose for the new vessel. In September 1950 it was officially reported that the new ship would be completed under a new name, to shuttle 12,000 troops per voyage to Korea, in support of the UN policing contingent. Given the much publicised military investment this was hardly a surprise but to everyone’s, and perhaps most especially William Francis Gibbs’ relief, the suggestion was dropped two months later and progress towards her civilian role could continue unabated.

Although First Lady Bess Truman was invited to name the new vessel, political sensibilities intervened, and the offer was declined just three weeks before the launch. Her substitute would be Lucille Connolly, wife of the popular Texas Senator who performed the ceremony on 23rd June 1951 with the ship 70% complete. The process of flooding the building dock had actually commenced almost fifty four hours earlier. Photographs of the event show the ceremonial party on a lofty platform with a seemingly rejected William Francis Gibbs standing impassively below.

On 14th May 1951, with a nervous but excited William Francis Gibbs onboard, United States edged out of Newport News on preliminary sea trials. Despite problems with an overheating bearing, they were deemed a great success. In early June, with 1,700 guests, again including Gibbs, comprising mainly media and United States Lines personnel, she undertook main sea trials off the Virginia Capes. Her true power output and speed remained classified until the late 1960s but showed she achieved 39.38 knots during one timed run. Further, unsubstantiated reports indicated a speed of 42 knots. Either way Gibbs had his record breaker.

Unlike foreign counterparts, there was no ambiguity concerning the funding of the United States. The $78 million investment was provided by the US Government, with the majority from US Navy coffers, which owned the ship but leased her to United States Lines. She was handed over at the end of June and after a gala reception steamed out of her home port of New York at noon on 3rd July 1952 on a maiden Atlantic crossing. Amongst the passengers was a Mr W. F. Gibbs, the only voyage he made on his ‘big ship’.

Despite the usual statements emanating from those involved it was self-evident that the new flagship could and almost certainly would eclipse Queen Mary’s fourteen year old record for the fastest transatlantic passage. The question was just how hard the ship would be pushed on that maiden passage. Some suggested she would just capture the Blue Riband by the slenderest margin and then beat that record in increments over subsequent years. In truth however fast she travelled she could not beat the aircraft proliferating in the skies above. Under Gibbs’ personal gaze and supervision, Chief Engineer Bill Kaiser steadily ramped up the power day by day claiming the Blue Riband on the morning of 7th July 1952 with an average speed of 35.59 knots. She had taken 10 hours off Queen Mary’s previous record run. William Francis Gibbs was satisfied.

Although she broke the westbound record on her return and rumours abounded that she had plenty in reserve, United States never made another Blue Riband attempt. Given the expense and excessive stresses applied to the hull it was a prudent decision. Although he never sailed on her again, Gibbs’ infatuation with his ‘big ship’ remained. He telephoned the ship daily, speaking to both the Commodore and, perhaps even more importantly, his good friend the Chief Engineer. Each time United States docked at New York he would invariably take a limousine to see her sail in past the Narrows and then be whisked down to Pier 86 for a visit (inspection?) and face to face discussions. Fuel samples were taken, notes scrawled. When she sailed out, a tall gaunt figure, invariably wearing a broad rimmed felt hat and long coat, would be seen dreamily gazing from the pier’s outer apron.

Of course Gibbs’ work did not stop with United States. Almost immediately he produced designs for a fine pair of liners for Grace Line’s South America service. Like their pre-war predecessors the ships were called Santa Rosa and Santa Paula and displayed many hallmarks from United States. Even more ambitiously Gibbs & Cox developed two further vessels of similar size and speed to United States. Initiated in 1956 and provided with congressional funding two years later, the plans involved a replacement for United States Lines’ America (which was designated that predecessor’s name) and a vessel for American President Line’s trans-pacific service provisionally called President Washington.

The new America was essentially a facsimile of the United States, whilst President Washington was 10,000 tons smaller but shared many of the national flagship’s characteristics.

Perhaps inevitably the projects ultimately foundered, the United States lines’ ship because of a dispute over the new America’s service speed and related funding, the APL ship in part because that company felt the design failed to reflect their routes specific requirements or include the latest technical refinements.

In 1953 Gibbs was awarded the Franklin Inst-itute’s Franklin Medal (above) for outstanding services to science and in 1955 he was awarded the first Elmer A. Sperry Award.

Throughout this period Gibb’s ‘Big U’ traversed the Atlantic. From 1963 she operated in tandem with the new French flagship France whose similar service speed and modern décor created a well-matched team. However, the end of the ocean liner was approaching. Like most ships of state, United States required a substantial operating subsidy. In the era of jet aircraft state funding of ocean liners was non-essential and steadily reduced. When the lucrative contract to transport service personnel between the US and Germany was also terminated the writing was on the wall.

With dwindling reservations and increasing fuel and labour costs it was simply a matter of time. As the ‘Big U’ edged towards obscurity her designer was also nearing the end of his life. The United States last master, Commodore Leroy J. Alexanderson, noted that although the daily telephone calls persisted, it was often one of Gibbs’ subordinates at the end of the line. He was told that Gibbs was too busy or attending a meeting, in fact the ageing naval architect was in hospital.

Fortunately, the great man never had to witness his finest achievement’s premature withdrawal from service in 1969, or the subsequent protracted decay. William Francis Gibbs died on 6th September 1967 at the age of 81 and was buried alongside his brother, even in death they were inseparable. On the next eastbound voyage, Commodore Alexanderson persisted with a time-honoured tradition. As she passed the Gibbs & Cox offices at 21 West Street in Lower Manhattan, United States bellowed three blasts from her mighty whistles whilst the Commodore stood implacably and saluted from the port bridge wing. That day they reverberated with a particularly melancholy timbre.

Fulton-Gibbs Hall, the marine engineering building at the United States Merchant Marine Academy at Kings Point, New York, is named in honour or Gibbs, along with Robert Fulton. The Gibbs Brothers Medal, awarded by the United States National Academy of Sciences for outstanding contributions in the field of naval architecture and marine engineering, was established by a gift from Gibbs and his brother.

Gibbs’ granddaughter Susan L. Gibbs is now President of the United States Conservancy who are trying to restore the ‘Big U’.

Comments

Sorry, comments are closed for this item