A much loved Great Lakes Ferry lives on

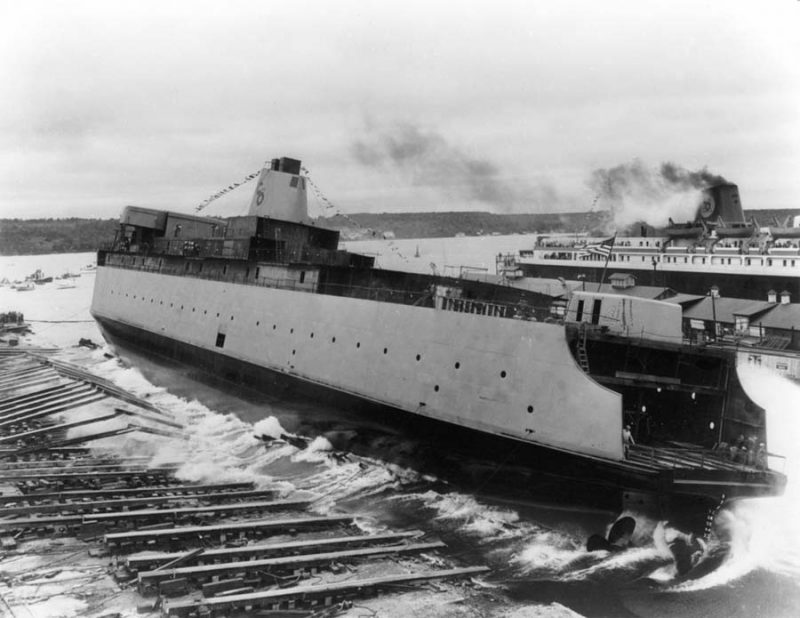

On September 6th 1952, twin ships were christened at the Christy Corporation ship yard in Sturgeon Bay, Wisconsin. It was a business-like ploy by the new owners (the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway Company) to save a little money on commissioning costs, for only the S. S. Badger was launched that day, her sister, the S. S. Spartan had in fact been launched eight months earlier. Now only the Badger remains in operation and her survival and continuing success is truly a remarkable story. The S. S. Badger is the very last link to the days when the Great Lakes of America were criss-crossed by large ferries, specifically designed to carry not only railway engines and railcars, but also motor vehicles, a type of ship pioneered by American shipyards in the 1920s and subsequently replicated all over the world where the need occurred.

Badger and her sister-ship Spartan were delivered to their owners for operation across the Lake Michigan, linking Ludington, Michigan, to Milwaukee, Kewaunee, and Manitowoc, Wisconsin. The link from Ludington to Manitowoc was to prove particularly important, for it joined up not only a rail network, but also part of the highway network, known as US route 10. Built in 1926, this was one of the first long distance roads across the continent and it linked Detroit with Seattle on the Pacific Coast. Today, the current owners (the Lake Michigan Car Ferry Service) are proud to have her officially designated as part of US route 10, described as being ‘the continuance route’ by the United States Department of Highways and Transportation. The vessel now proudly displays the ‘US 10’ badge prominently on her stern cargo door, immediately above the vehicle ramp for all to see as they drive onboard.

Nowadays, this is just one of the accolades which have come her way. She is designated a ‘Mechanical Engineering Landmark’ by the American Society of Mechanical Engineers, and was placed on the National Register of Historical Places by the U S Department of the Interior in 2009. In addition, she was named ‘Ship of the Year’ by the Steamship Historical Society in 2002, and was most recently, on 22nd February 2016, declared a ‘National Historical Landmark’ by the National Park Service of America. It seems nearly superfluous to mention that ‘Trip Advisor’ also awarded her a ‘certificate of excellence’ for 2018!

Probably the most startling fact concerning the S. S. Badger is that she is the last seagoing vessel still operating commercially in the United States which is powered by coal fuelled steam engines. Her source of fuel is indeed nothing more than domestic coal, and the perseverance of her owners in that respect has been remarkable, when considering all the issues regarding the enforcement of legislation regarding ‘green’ energy on board ships. Given that ‘LMC’ recognised the uniqueness of the twin 3500HP ‘Skinner’ steeple compound unaflow steam engines and 4 ‘Foster Wheeler’ coal fired marine boilers, it is hardly surprising that her propulsion system is a large part of what makes the ship both unique and memorable. The historical plaque mounted on board the ship notes that the engines represent one of the last types of reciprocating marine steam built by the Skinner Engine Company and that most unaflow engines are single expansion. The Badger’s engines feature tandem high and low pressure cylinders separated by a common head, and the four type D marine boilers which supply 470 PSIG steam engines are amongst the last coal fired marine boilers ever built. Undoubtedly one factor which has made her survival not only possible but also financially feasible has been the original hull design and heavy scantlings. This is a ship built to withstand the rigours of many winters spent traversing the inhospitable and often ice laden waters of the Great Lakes. Strength-ened to ‘Ice Class’, and designed as an ice breaker, to this day the hull thickness of the steel is well within the required standards, a blessing not often accorded to ships in near continuous service for 63 years.

Car ferries first began operating across the Great Lakes in 1892, when the Ann Harbour Railroad first instituted the transport of loaded rail cars from Frankfort (Michigan) to Kewaunee (Wisconsin). But that company was in fact preceded by the Flint and Pere Marquette Railway Company, who began cargo ship and passenger operations as early as 1875 when they chartered the 175 foot paddle steamer James Sherman to ship general cargo and passengers from Ludington to Sheboyan. Twenty two years later, this prospering company launched into service a new 350 foot steel hulled vessel, purpose built for a cross lake rail car ferry service. She was named Pere Marquette after the famous Jesuit priest who helped found what is now Michigan State and was a ground breaking design of ship which set the standard for further vessels of this type well into the 20th Century both in America and around the world.

As the new century progressed, ferry services grew exponentially whilst the American mid and far west economies expanded, despite the intervention of the First World War and then the Great Depression. By the middle of the 20th century, rail and car ferry services across the Great Lakes were reaching their peak, and the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad Company, who had taken over the Pere Marquette operation, ordered their final two ships which were to be the biggest and the best by far, the Spartan and the Badger. Curiously, the names for the vessels came about by way of satisfying the intense rivalry of two opposing universities in the linked mid-western states. The Badger was named after the University of Wisconsin’s athletics team the ‘Wisconsin Badgers’, whereas, the Spartan’s name derived from the name given to the sports teams of the University of Michigan.

Badger’s early days were indeed concentrated on shifting railroad wagons to and fro across Lake Michigan, however, by the 1960s technological developments in both the railroad and highway systems, together with the growth in air travel, began to undermine the role of the Great Lakes car ferries. Improved rail systems around the bottleneck at Chicago and more efficient track switching devices where required, dramatically reduced any time gained by using the ferry crossings. An ever expanding network of freeways and interstate highways also negated much of the time savings that a cross lake voyage could deliver, and the upshot of those developments was to see much of the transported freight traversing the North American Continent diverted from the railroad systems onto the highway network instead. Rail traffic thus began to dwindle rapidly across the Great Lakes ferry systems in general, as services were reduced and then ceased all together. Successive railroad companies either merged and downsized, or suffered bankruptcy and failure, and as a consequence rail and car ferry services began to dwindle rapidly. By 1983, the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad Company, with their fleet reduced to just three vessels, sold out to the ‘Michigan-Wisconsin Transportation Company’, selling the Badger, the Spartan and the City of Midland 41 for the princely sum of one dollar per vessel. Despite a valiant effort, they in turn eventually became bankrupt and ceased operations completely in 1990. The ships were then laid up and for a period of two years no ferry services ran whatsoever, and the Badger and her sister’s fate hung in the balance.

In 1991, an entrepreneur by the name of Charles Conrad saw the possibilities that remained and brought the three remaining ships out of bankruptcy and formed the ‘Lake Michigan Car Ferry Company’. The purpose of this was to re-establish the Ludington to Manitowoc link on Lake Michigan, and to secure the future of at least one of the last iconic car ferries of the Great Lakes system. In doing so, the company also threw an economic lifeline to the port communities on either side of the lake, communities which clearly identify themselves with the ongoing success of the S. S. Badger. Sadly there could be no reprieve for her sister ship, the Spartan, or for the City of Midland 41. However, to this day the Spartan still sits at her berth just astern of the ferry terminal in Ludington, slowly being cannibalised for spare parts as and when needed by the Badger. Charles Conrad and his employees then set about re-inventing the S. S. Badger for a further career as purely a passenger and motor vehicle carrying ship. The rail tracks were stripped out, the vehicle decks and passengers spaces reconfigured and modernised and in 1992 she again set sail, this time on a seasonal basis only, and dedicated to the Ludington/ Manitowoc crossing and US route 10. The carrying figures for that first year wildly exceeded their expectations, and so the S. S. Badger once again became a permanent feature of Lake Michigan. In 1994, an amicable ‘in house’ buyout of the company occurred, with a group of his executives headed up by the son in law of Charles Conrad, Robert Manglitz, taking over the reins. Charles Conrad then retired to Florida like all good American entrepreneurs do, leaving Manglitz and his group to remain firmly in control, where they remain to this day.

Ferry bound traffic nowadays comprises mainly of East and West bound tourists, many still anxious to avoid the urban sprawl of Chicago just as in former days, but Badger also carries a substantial amount of freight vehicles, carrying anything from wind turbine towers to Clydesdale horses. To cater for a passenger load of up to 650 persons, the public areas have been continually upgraded over the years, and she can boast of having as many as 40 private staterooms, a movie theatre, a bingo hall and of course full restaurant, lounge and cafeteria facilities. An onboard museum tells the story of the ship and her association with Lake Michigan and no doubt gives passengers an understanding and appreciation of her place in the maritime history of the United States. Like older passenger ferries, she also boasts good outdoor spaces around the upper decks, her passengers thus able to fully enjoy the summertime pleasures of crossing Lake Michigan, or viewing more closely a varied and beautiful coastline, when she performs one of her frequent and popular evening shoreline cruises.

Over time, the ship has had to overcome many problems, and by 2010, there was an increasing demand that despite the ship’s unique place in maritime history, she had to comply with current marine environmental standards. One of the most pressing matters to be dealt with was the fact that every day the ship had to dispose of nearly 4 tons of coal ash. Another issue was a requirement to lower airborne pollution levels and at the same time improve stokehold and boiler efficiency. The issue of how to improve and clean up coal fired airborne emissions was tackled during the 2014 winter overhaul and lay-up period, and met with regulatory approval in time for the 2014 season. This work included the installation of computerised control systems and more sophisticated air circulation methods and equipment, in order to improve the efficiency of the coal burn itself, the whole operation being an interesting look into how best to preserve an old, historic and yet fully functional steam engine, and at the same time marry it with the requirements of legislation and modern efficiency.

In 2014, the Environmental Protection Agency also demanded that the problem of coal ash disposal be fully resolved to meet their exacting standards. Previously, this had simply been removed by mixing the ash with water, and then dumping the slurry into the waters of Lake Michigan, plainly a practise that had to stop! This task therefore became essential work to be carried out during the 2014/15 winter overhaul period. Now, after the installation of a new onboard collection system, and the removal of the old system, once the ash has been raked out of the fire chambers, it is automatically transferred up and along pipelines to the vehicle deck, where it safely stored in containment bins, ready for offloading at the end of the working day. This exercise was also successful and the 2015 summer sailing season proceeded on time. The Company plans to sell on this compacted coal ash material, perhaps for future use in a cement making process and so, at a cost in excess of 2.2 million dollars, two environmental problem were resolved and a unique service protected for future generations. Operating a ship of this age comes with many challenges, and even in the winter of 2015/2016, the Badger had to undergo the detailed and thorough special 5 yearly survey and dry dock, which was undertaken at her place of construction in Sturgeon Bay, Wisconsin.

When a working ship has reached such a venerable age, it is interesting to note how well she can cope with the demands of a daily schedule of sailing, given the advanced age of her mechanical equipment and modern ferry operators would do well to consider her record in this respect. In the sailing season of 2015 (April to October), according to the company, not one sailing was cancelled for either weather related or technical reasons and in 2004, it was reported in a local newspaper that from 1992 (the start of the LMC operations) until that date (a twelve year period), not one sailing had been cancelled for any reason whatsoever. Perfect reliability is not always attainable however, and on 9th August 2008, the Badger suffered a stern bearing failure on the port propeller shaft, resulting in a week of cancelled sailings. The ship limped north a day later to a Sturgeon Bay repair facility, and despite the lack of an available dry dock, repairs by a team of divers were carried out and she re-entered service again on the 15th August. On the very first day of the 2012 sailing season she also suffered a minor mishap, when on final approach towards the Manitowoc terminal, she grounded on a shoal patch inside the harbour limits. Either during this gentle grounding, or in the efforts to refloat her, she suffered a seized and damaged piston. Nevertheless, with the aid of a tug she was soon refloated, and according to press reports, was back in service within 4 hours. It appears that the sailing delay was observed with nothing more than humorous patience by passengers who were due to either disembark or board the ferry and the incident warranted no more than a passing mention in the local newspapers and media. Over the decades therefore, these statistics of punctuality are truly remarkable and are a testament to the endurance of the ship’s hull and its unique propulsion system, and to the dedication of the company employees.

What makes the Badgers success all the more unique, is that she continues to be profitable, without any operational subsidy whatsoever from either State or National governments, in contrast to several other Great Lakes ferry operations, which either struggle or have already failed. It would appear that the willingness of both the Michigan and Wisconsin governments not to interfere and where possible to assist the company to comply with the most appropriate legislation, but without financial support, has been a part of a successful formula for the ship. The LMC Management have clearly identified their market niche in the seasonal tourist business, augmented by some commercial traffic, and trained and motivated their staff accordingly. Deservedly therefore, It seems that the story of the S. S. Badger will continue for some time to come and her place in living maritime history will be secure.

Comments

Sorry, comments are closed for this item