Many passenger liners have been labelled ‘Ship of State’, but it is doubtful any have more readily captured the collective spirit of a nation, or tapped into its raw emotion, more evocatively than Nieuw Amsterdam. The date was 10th April 1946. The place, Rotterdam. The ship, bedecked with signal flags and sporting recently painted yellow, green and white funnels above her tired, rust streaked wartime grey, was returning to her home port for the first time in almost seven years. To the thousands lining the shore and cheering from every boat and vantage point, the return of their flagship symbolised a final liberation from the travails of war. It was a cathartic experience, for a city laid waste by the Luftwaffe in 1940 and later Allied bombing sorties. Many of the spectators may also have endured Hongerwinter, the great famine which had afflicted the country’s western provinces in the final, fateful, winter of the war. Despite the post-war deprivation the ship was a talisman, tangible evidence of a country getting back on its feet. No wonder thereafter she was affectionately referred to as ‘The Darling of the Dutch‘.

Nieuw Amsterdam was ordered on 5th December 1935 by Nederlandsch-Amerikaansche Stoomvaart Maatschappij, more commonly referred to as Holland America Line (HAL) and the Netherlands’ principal transatlantic operator. Like most shipping lines, HAL had experienced a slump in passengers and profits since the Wall Street crash of 1929 and the ensuing Great Depression. Nevertheless, under the pivotal stewardship of a new chairman, Willem van der Vorm, the line had been successfully restructured from 1933, old tonnage laid up or sold and the finances stabilised and ultimately secured. This was essential. Unlike its rivals HAL was unable to obtain state subsidies or favourable loans based on national prestige or potential military use. In fact one of the new liner’s marketing slogans, ‘The peace ship‘, reflected the fact there was no naval consideration or input into her design. By the mid-1930s however, the Dutch government was deeply concerned about rising unemployment, especially in the Rotterdam region. As a solution they looked to bolster the country’s beleaguered shipbuilding industry and so utilising his broad business experience and influential contacts, Willem van der Vorm was able to secure state funding towards the construction costs of the new vessel.

Given the long association between shipyard and shipping line, it was perhaps inevitable that the building contract was awarded to De Rotterdamsche Droogdok Maatschappij (Rotterdam Drydock Company). So keen were they to secure the order that the yard’s workforce took a voluntary pay cut. In return received guaranteed work at a time of widespread austerity. Significantly, one of the stipulations applied to the government loan was that all construction, engineering, and craftsmanship should where possible, be sourced from within the Netherlands. By implication this meant that elements of the ship were sub-contracted to other yards, as with the boilers and turbines (in this case N.V. Koninklijke Maatschappij, the ’De Schelde’ shipyard based in Flushing) which were built under licence, using plans supplied by the British based designers.

Within a month of the contract being awarded the first keel plates had been laid and fifteen months later, on 10th April 1937, the 758ft long hull was launched into the Maas, having been named by Queen Wilhelmina. Although the company initially allocated the name Prinsendam for their new flagship (Stellendam was also considered), by the time of her launch this had been changed to Nieuw Amsterdam, referring to the 17th century Dutch settlement at the tip of Manhattan Island that ultimately spawned New York. It was also a tribute to her 1906 vintage, 16,967 grt namesake, a Harland & Wolff built liner that had been scrapped in 1932.

Technical basin trials were undertaken in late March, before Nieuw Amsterdam left the shipyard on 23rd April 1938 for sea trials in the North Sea. Joining the engineers and observers was an entourage of VIPs, comprising the Dutch Prime Minister and the ambassadors of France, Belgium, Great Britain and Germany. Externally she offered one of the most simple, balanced and beautiful silhouettes of any 1930s passenger liner, arguably amongst the finest of all time. Her long svelte hull, designed by the nation’s foremost naval architect H. Prins, neatly curved forward superstructure and gently terraced aft decks, were topped by two perfectly proportioned 41 foot high funnels, bracketed by tall, raked, fore and main masts. All machinery exhaust smoke and gases were routed through the forward funnel, which initially incorporated six vertical vents, to increase airflow and thereby supposedly take smoke and smuts up and away from the aft decks. In practise the design failed to work and within a year the openings were plated over. The aft funnel was a dummy which contained freshwater filters, suction ventilators for the galley, fuel and sanitary tanks.

The trials primarily tested the new liner’s auxiliary and main propulsion machinery. These comprised a mix of conventional and innovative technology. Six Yarrow type water tube boilers were located forward of the main propulsion machinery, which consisted of two sets of triple expansion Parsons turbines. The resulting 34,000shp of combined power was transferred through a combination of single and double reduction gearing to twin shafts, which propelled the new liner to a maximum speed of 22.8 knots over the measured mile. Although relatively modest by comparison with the great German, French, British and Italian liners of the era, she was the most powerful twin-screw liner afloat and the results proved more than adequate for the 20.5 knots required in transatlantic service. The service speed could be achieved using just five of the six boilers, allowing a degree of redundancy and scope for maintenance and repairs to be undertaken underway.

Steam drawn from the boilers was used to supply the laundry, for general hotel services and pre-heating the viscous bunker fuel. This was achieved by a sophisticated and innovative ‘bleeding’ system, at various stages of the turbine process. Electrical power was provided by three 850kW turbo-generators at sea, and by two 425 kW Werkspoor designed and built diesel generators when in port. HAL were sufficiently satisfied with the trials performance to formally accept Nieuw Amsterdam on her return to the shipyard.

On the evening of 9th May 1938 the new flagship embarked her first complement of passengers. As scheduled, she slipped her lines shortly after midnight the following morning, and with Commodore Captain Johannes J. Bijl in command, eased away from the Wilhelminakade terminal, bound for Boulogne-sur-Mer, Southampton and ultimately New York. Those maiden voyagers settled into a ship of great style.

There was a maximum capacity of 1,220 berths, divided into three classes (556 Cabin, 455 Tourist and 209 Third). The accommodation, in 546 cabins, ranged from luxury suites, situated centrally on Lower Promenade Deck and each named after a Dutch province, to four berth Third Class cabins down on C deck. Each of the named Cabin Class suite had its own unique décor and included a bedroom, separate sitting room alcove, walk in wardrobe and a bathroom with full tub bath and overhead shower. Almost 70% of the cabins on board had their own private bathroom facilities, including all of Cabin Class (a first on the Atlantic), most of Tourist Class and even, exceptionally, some in Third Class. Even the cheapest accommodation included a basin with hot and cold running water and individual fresh air and temperature controls. Tourist Class cabins frequently offered similar dimensions and facilities to their Cabin Class equivalents, as befitting a ship designed with off season, one-class cruising in mind.

Although less than half the size of Queen Mary or Normandie, the 36,287grt Nieuw Amsterdam felt a spacious vessel. There were eleven passenger decks in total, with the majority of the twenty-three public rooms located on Promenade and Upper Promenade Decks. Like Normandie, and as introduced on Albert Ballin’s pre-First World War ‘big three’, Nieuw Amsterdam featured divided engine room uptakes. These facilitated an unimpeded central axial arrangement of public rooms, many of which were two decks high and considered amongst the finest examples afloat.

Farthest forward on Promenade deck, ensconced behind the forward facing wraparound glazed promenade, was the Cabin Class theatre. Only the second permanently installed room of its kind on board a passenger ship, after the Normandie, its ovoid ‘egg’ shape tapered towards the forward screen/stage, providing unimpeded sight lines for the 350 deep cushioned chairs. Utilising the latest sound-proofing materials and amplification technology the designers optimised the acoustics for a range of roles, from cinema to recitals and occasional stage productions. This room also benefitted from the ships’ most trumpeted technical innovation, together with the dining rooms of all three classes the theatre was air-conditioned, part of the most comprehensive system of its type afloat.

Sixteen of the country’s leading architects and artists were commissioned to design and decorate the new ship‘s public rooms. Primarily these followed fashionable Art Deco themes, especially in Cabin Class, although there were also examples of the modernist De Stijl style in Tourist Class.

Amongst the most significant rooms was the Grand Hall, designed by Hendrik Wijdeveld and situated aft of the theatre. A lavish contemporary brochure referred to this two-deck high lounge in suitably flowery language, “The room is a symphony in gray that provides a perfect foil to the habiliments of post-prandial activities, with emphasis on the distaff side”. By day it was showered in light from large engraved, stainless steel framed windows. At night, the recessed lighting and uplighters provided a deliberately understated venue, fulfilling Wijdeveld’s intention that passengers rather than decor should create the colour and glamour. For veteran and prudish passengers, used to the traditional décor and artwork associated with the ship’s predecessors, the Cubist chairs and vibrant murals on the forward and aft bulkheads by Gerard Roling, featuring nudes on horseback in various states of ‘harmony and disharmony‘, must have come as quite a shock. Craning their heads, they may have been similarly perturbed to discover John Raedecker’s cast aluminium ceiling, telling the story of life in a series of nude half-reliefs. According to the brochure it comprised, “male and female figures, supplemented by bird motifs, the composition ascends and descends the scale of human existence, from childhood to old age”.

Such passengers may have felt more comfortable in the 52 x 60ft smoking room, located aft via a central corridor which was flanked by the Cabin Class card room and library, also by Wijdeveld, and an even more impressive lobby. Designed by Frits A. Eschauzier, the smoking room’s walnut panelling, standard lamps, high backed Moroccan leather armchairs, terracotta sofas and tan carpet, were as solidly dependable as the cast iron fireplace. Although historically a male domain, its heavy atmosphere was lightened by Verandas on either flank, and a modern bar.

Directly above the smoking room, situated aft on Upper Promenade Deck, was the Ritz-Carlton Café. It was accessed via a distinctive ebony and bronze Y-shaped staircase, which led to entrance doors on either side of a secluded, intimate cocktail bar. Hendrik Wijdeveld was once again responsible for the décor and imbued the room with a light, fresh atmosphere. Sweeping views of the sea and sky were provided through floor to ceiling windows on each flank and a further dozen on the rear bulkhead of the adjacent veranda. Wijdeveld amplified the natural daylight by using white furniture and gold wall panels, with matching spindly pillars. The oval dance floor sat below a painted wooden ceiling, with its orchestra bandstand screened from the cocktail bar by an ebony and anodised gold panel. Two large fresco panels by Han Hulsbergen decorated each side of the entrance, symbolising dawn and dusk, through depictions of classical figures.

To many the most distinctive Nieuw Amsterdam public room was the antithesis of the Wijdeveld’s daylight drenched Ritz-Carlton Café. In fact, it had no windows at all. Bracketed by first class cabins running along each flank, the two-deck high Cabin Class restaurant was designed by Jac. F. Semey, with the express intention that patrons should forget they were at sea. Despite the lack of fenestration, it was far from sombre, with elaborate frosted Murano-glass light fittings illuminating a room of rich and diverse colour, including a distinctive tan-hide Moroccan leather ceiling, gold leaf pillars and ivory coloured walls. Seated in satinwood furniture upon a deep blue carpet, the ploy was to divert passengers’ focus away from the turbulent North Atlantic, so that they could then concentrate on the gourmet food on offer. As they dined, they were serenaded by the ship’s orchestra, perched in a gallery above the main entrance, which was flanked by Joep Nicolas’ intricate burnt glass depictions of Arcadian pastoral scenes. The room felt even larger thanks to the clever use of twenty painted mirrors, interspersed between further Nicolas vermurial panels. The overall affect created one of the most distinctive and stylish dining venues afloat.

If Cabin Class public rooms inevitably drew accolades it was in Tourist Class that the more avant-garde approach found its niche. With an inherently egalitarian outlook, the De Stijl groups’ fresh decorative approach was best exemplified on board Nieuw Amsterdam in the work of Jacob Johannes Pieter Oud, commonly referred to as J.J.P. The ’poetic functionalism’ that he had brought to the design of workers residential projects in Rotterdam, manifested itself in a range of fun, informal and brightly coloured cabins and public rooms, especially the Tourist Class cocktail bar.

Life onboard followed a well-worn pattern but with some unique distractions. Although limited by modern standards, facilities and formalised events were advertised in a daily program, printed on board. For the active in Cabin Class, a blue Delft tile lined indoor swimming pool (Tourist and Third Class had their own on C Deck) and adjacent squash court, were open from 0700 to 1230 and 1400 to 1900 daily, down on E deck. Alternatively, at the top of the ship was a fully equipped gymnasium, complete with the most modern equipment and an instructor, which could be accessed during the same opening hours. Outdoor pursuits included trap shooting, on the aft part of Upper Promenade Deck, weather permitting, and the usual array of deck tennis, golf and shuffleboard. For avid competitors, a tournament of deck games was organised daily from 1100 up on Sports Deck, with finals and associated awards ceremonies, arranged for the last full day at sea. As a post exercise relaxant, or for straightforward pampering, passengers could indulge in the supervised Turkish Bath facilities on E deck, in essence the spa experience of its day.

Less energetic competitors could participate in the Bridge Party, run daily from 1500 in the card room, meanwhile the ‘Nieuw Amsterdam Jockey Club’ organised periodic horse racing events, in which wooden horses were moved by a dutiful deck steward, on Upper Promenade Deck.

For entertainment Nieuw Amsterdam offered the latest movie releases in the theatre/cinema. On one westbound voyage, departing 27th August 1938, screenings at 1700 and 2130 included ’Keep Smiling’ starring Jane Withers and Gloria Stuart, ‘Letter of Introduction’ featuring Edgar Bergen, Charlie McCarthy and Andrea Leeds, then on the last evening out, Mickey Rooney, Lewis Stone and Cecelia Parker in ‘Judge Hardy’s Children’. Dining, then as now, was a major component of shipboard life. Traditional morning bullion on deck and afternoon tea in the Grand Hall supplemented six course luncheons and dinners in the main restaurant. Evening entertainment centred on conversation in the smoking room with music and dancing in the Grand Hall, gravitating from midnight to the Ritz-Carlton room. A recital might take place in any of these venues.

Of course, many eschewed any form of ‘organised’ activities or exercise. To these passengers the prospect of six days at sea, to be wiled away at leisure, away from the stresses and strains of normal life, meant doing very little. For others there was only trepidation. In the era before mass aircraft travel, when sailing across ‘The Pond’ was literally the only way to cross. Every voyage included those tourists and businessmen for whom an ocean crossing, no matter how benign the conditions, was a necessary but daunting endurance test, rather than a pleasure.

Dressed overall in signal flags, Nieuw Amsterdam arrived in New York harbour on 16th May 1938. Several tugs escorted her up past the Battery but there was none of the adulation afforded to her larger, more exulted contemporaries. In part this may have been because she arrived half a day earlier than scheduled, nevertheless bathed in evening sunlight the ship looked magnificent as she sailed down the Hudson and was nudged into the company’s 5th Street Hoboken Pier, on the New Jersey shoreline. She had officially crossed the Atlantic in a whisker under six days (5 days, 23 hours and 45 minutes) at an impressive average speed of 21.7 knots. Over subsequent days HAL opened her up to the inquisitive public, in return for a donation to local seaman’s charities.

Nieuw Amsterdam quickly settled into her new role. Departure from Hoboken was generally timed for midday on a Tuesday, arriving in her home port a week later after anchoring at Plymouth on the Monday afternoon and Boulogne on the last morning out. The following Friday night passengers embarked for the traditional 1205am Saturday morning departure from Rotterdam, calling at Boulogne and Southampton later the same day and arrived at Hoboken on the subsequent Friday afternoon. As usual in that era there were leisurely turnarounds at both terminal ports. A round trip Cabin Class ticket cost from $474 in high season and about $50 less in low season. Passage in Tourist and Third Class was available from $288 and $207 respectively, in high season. Tourist Class offered particularly good value for money. Ironically, given later developments, HAL also became official U.S. agent for Royal Dutch Air Lines (K.L.M.) from 1st September 1938, allowing passengers to book onward flights to European, Dutch East and West Indian territories and even Australia.

Prudently Nieuw Amsterdam had always been intended for one-class, off season cruising. With a reduced clientele of around 750 and with the partitions between Cabin and Tourist Class public rooms temporarily opened, HAL offered an ambitious series of cruises over the winter of 1938/39. If back-to-back twenty five day voyages to Rio, departing on 17th December and 14th January, including three days and two nights moored at the then Brazilian capital, weren’t enough, they were followed by a full circumnavigation of South America. This voyage, advertised as the highlight of HAL’s ‘Spotless Fleet’ season of cruises, was arranged in conjunction with American Express Travel Services, with fares starting from $720.

At 1700 on Saturday 11th February 1939, Nieuw Amsterdam cast off from her Hoboken Pier and headed south, leaving a frigid New York behind, and steamed to Havana, then Cristobal and Colon before transitting the Panama Canal. Once in the Pacific she stopped at Balboa, then Callao and Valparaiso, ultimately navigating the southern extremities of the continent, transitting the spectacular Chilean fjords, and calling at Punta Arenas in the Straits of Magellan. North bound she docked at Buenos Aires and Montevideo on the River Plate, then Santos, a third call in as many months at Rio de Janeiro, and then Bahia in Brazil. After leisurely days anchored off St Thomas and Nassau, she arrived back at Hoboken 46 days after setting off, having steamed 14,103 nautical miles.

In the spring of 1939 Nieuw Amsterdam recommenced the transatlantic ferry service. She replaced the veteran Rotterdam (IV) of 1908 and sailed alongside the three funnelled Statendam, and slightly smaller Volendam and Veendam. These ships were joined by a pair of new 10,700grt combination liners, the Noordam and Zaandam, which in addition to six holds of cargo offered 148 First Class berths. The new flagship bucked the trend of many contemporaries and proved as profitable as she was beautiful. Encouraged by her performance van der Vorm and his co-directors considered a running mate, of similar dimensions, speed and capacity but with a more streamlined, ultra-modern profile. Referred to variously as the ‘1940/41’ and ‘Rotterdam’ project, the intended ship would help HAL provide a balanced, three ship service across the Atlantic. Like so many similar plans it was initially delayed by funding issues (there was no longer the political imperative to subsidise the shipbuilding and fitting out industries), and ultimately scuppered by the advent of war.

Holland America maintained it’s schedules throughout that fateful summer. Nieuw Amsterdam arrived in New York on 1st September 1939, the day Germany invaded Poland, with 1,286 passengers, including a high proportion of Jewish evacuees. Such was the desperate demand for berths that mattresses were spread across the children’s playroom and other public rooms to accommodate excess passengers. With her name and ‘Holland’ prominently painted on each black flank Nieuw Amsterdam returned to Europe on 6th September. The subsequent westbound voyage, the thirty fifth transatlantic crossing of her fledgling career, would be her last for eight years. Despite her neutral status and following the shocking sinking of the Athenia and threats to merchant shipping in general, HAL deemed it too dangerous to continue the service. Nieuw Amsterdam was laid up at her Hoboken pier.

After a reasonable pause, the Dutch felt it was safe to send their new flagship on cruises. Nieuw Amsterdam commenced a program of ‘Peace cruises’ from Hoboken on 21st October which sailed to Bermuda until mid-November but then shifted to the Caribbean, starting with a Christmas cruise departing on 23rd December 1939. Over the ensuing winter she was seen in a range of ports, from Cuba and the Bahamas to Venezuela. In such idyllic settings the European war seemed little more than a distant aberration. The cruises proved popular and so the season was extended through into the late spring of 1940, but events in her homeland would soon change these plans. Nieuw Amsterdam was on passage from La Guairá to Puerto Cabello on 10th May 1940 when her radio operator received an urgent message from company headquarters. The Netherlands had been invaded and was now directly embroiled in the war, so Captain Bijl was ordered to return to Hoboken post-haste, to await further instructions.

The German attacks on neutral Belgium and the Netherlands met brave but ultimately futile resistance. Under equipped and facing overwhelming aerial superiority, the Dutch surrendered following a devastating bombing offensive on Rotterdam. With the implied threat of attacks on other cities the decision was made to avoid further civilian casualties. In the interim Queen Wilhelmina and her ministers escaped to London, where they established a government in exile. Once more pressing issues had been addressed, they considered the fate of the country’s merchant fleet.

On 12th September 1940, the government formally requisitioned Nieuw Amsterdam from HAL and immediately offered her to the British Ministry of Transport. With management assigned to Cunard-White Star but retaining her Dutch crew and registry, HMT Nieuw Amsterdam was briefly sent to the Todd shipyards in Brooklyn. Sporting an all grey livery she then sailed to Halifax, for the installation of a degaussing strip to repel magnetic mines and a broad array of anti-aircraft guns. On 11th October she departed Nova Scotia, called briefly at Cape Town for bunkers and ultimately arrived in Singapore on 9th November, where the internal conversion was to be completed. It was whilst she was in the Far East that the majority of artwork, furniture and fittings were removed and unceremoniously dumped on the dockside. There was little room for sentiment as carpenters and dockworkers focussed on installing multi-tiered ‘standee’ bunks and canteen tables. The artwork and fittings were subsequently collated and shipped via Australia to San Francisco, where they were kept in storage for the duration of the war.

Bearing pennant number 5000 HMT Nieuw Amsterdam was commissioned on 22nd December 1940 and departed Singapore for Sydney on Christmas Eve. Just under one month later, on 23rd January, she sailed across the Tasman Sea to Auckland and Wellington, returning to Sydney with New Zealand troops. Those soldiers encountered a vessel that was unrecognisable from her peacetime incarnation.

On 4th February 1941 Nieuw Amsterdam left Sydney on her first trooping assignment, with reinforcements for the North Africa campaign. She accompanied the distinctly glamorous cast of convoy US9, namely Queen Mary, Mauretania and Aquitania. Two months later she sailed in even more exulted company. As well as Queen Mary and Mauretania she was joined by Ile de France and the new Queen Elizabeth, forming three columns, 1,000 yards apart, with the French and Dutch ships taking up station 800 yards aft of the Cunard trio. These five ’monsters’ comprised US 10, crossing the Indian Ocean at 20 knots as the largest troop-carrying convoy (about 22,000 men) of the entire war. The intense, tropical heat (promenade deck windows reputedly cracked) and cramped conditions were relentless, and with only limited time on deck per day it was a stifling, uncomfortable experience for the soldiers.

From May 1941 Nieuw Amsterdam was employed on a shuttle service between Durban and Suez, northbound with South African troops and south with the wounded and German and Italian prisoners of war. In June she had the dubious distinction of transporting the fleeing Greek royal family to wartime exile in South Africa. Towards the end of November, she joined one of the vast ‘Winston Specials’. Comprising 24 ships WS12 had sailed from Liverpool in late September, Nieuw Amsterdam joined the residual eighteen at Durban, travelling up the East African coast under the watchful eye of the battle cruiser Repulse and the battleship Revenge, before dispersing off Aden en route to Suez.

There was little change to her general deployment in 1942, although occasionally Nieuw Amsterdam would be seen in new locations. Perhaps the most exotic of these was Diego-Suarez, in the north of Madagascar, which many of the crew considered the most beautiful place the ship ever visited.

In March 1943 Nieuw Amsterdam crossed the Pacific and received a major refit in San Francisco, where boilers were re-tubed, propellers replaced, and new bunks installed. She returned to service with an increased capacity of 6,070 troops and smartened internally and externally by fresh coats of paint. Having spent the year in the Indian Ocean, ferrying troops back and forth between the Antipodes, South Africa, and Suez, she returned to San Francisco in October 1943 for yet more work. Like the Cunard Queens, Nieuw Amsterdam had been earmarked to ferry US troops to the UK, as part of the build up to Operation Overlord, the invasion of Normandy.

So, in March 1944 Nieuw Amsterdam found herself back plying across the Atlantic, however comparisons with her pre-war commercial service ended there. She primarily sailed outbound from New York and Halifax with GI’s and Canadian troops bound for Gourock on the Clyde, as the Allies built up their forces prior to D-Day and then pushed east through France, Belgium, and the Netherlands. Nieuw Amsterdam mainly sailed alone, using speed and a zig-zag course to evade enemy submarines. Her 8,600 troop capacity was six times greater than the peacetime complement and those who sailed on her were left with indelible, if hardly happy memories of the voyage.

Wijdeveld’s Grand Hall was now a six hundred berth dormitory, the egg-shaped theatre held almost four hundred more. Each of the spacious, deluxe suites was stripped bare and accommodated twenty two officers. Each soldier was assigned a 6ft x 2ft bunk, where they had to store all their equipment as well as sleep, in tiers up to eight high and separated by narrow access channels barely two feet across. It was a claustrophobic ordeal. Black humour abounded, with the experience frequently referred to in comparison to sardines packed into a tin. All that was missing was the oil.

In benign weather it was just about bearable, but when she encountered heavy seas, fear and seasickness made conditions all but intolerable. For those who had the stomach ‘meals’ were served on stand-up tables twice a day, in five shifts. The food on offer was generally unappetising but given the numbers to be catered for this was perhaps inevitable. Daily consumption included 240 gallons of powdered milk, 14,000 loaves, 13,000 eggs, 6,400 quarts of coffee and 1,000lb of bacon.

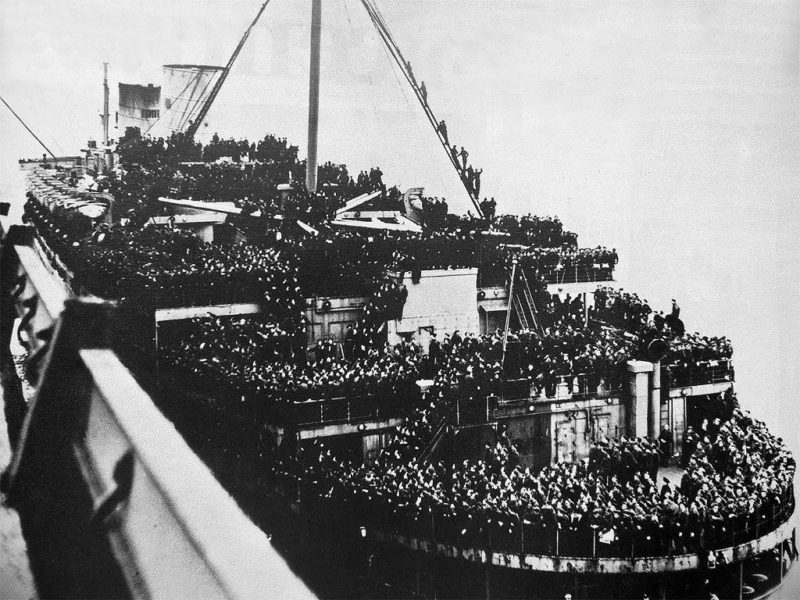

Normally on the first day out the general alarm would sound, and all troops were instructed to muster on deck. As the ship’s precious, life preserver clad human cargo filled every square foot of deck space, the dramatic scene was frequently captured for posterity by photographers. Otherwise, the men had little fresh air. When permitted, hundreds would crowd around impromptu dance and music routines, or boxing contests. Generally, however, they were confined below decks. Small wonder they were relieved to see the Scottish coast emerge on the horizon and get their feet on dry land.

Throughout that penultimate year of the war Nieuw Amsterdam was employed almost exclusively on the North Atlantic. The only exception was a solitary voyage from Gourock to Cape Town and back in August 1944. To this day its purpose remains a secret. For the Dutch contingent there was a morale boosting visit in May 1944 by HRH Princess Juliana, daughter of HRH Queen Wilhelmina. Having fled to Canada in 1940 she boarded the ship at Hoboken, for a tour and a buffet lunch with a selection of the ships’ officers and crew.

Thanks to the introduction of long-range Liberator and Short Sunderland coastal patrol aircraft, escort ships with advanced sonar and radar equipment, and perhaps most significantly the cracking of the German Enigma code, the U-Boat threat generally diminished in 1944. Nevertheless, in both December 1944 and early January 1945 Nieuw Amsterdam was targeted by submarines off the Canadian coast. In the latter case Captain Dobratz of U-1232 claimed to have fired three torpedoes at the speeding liner, fortunately for the 6,293 troops onboard all three slipped astern of her and exploded in her wake.

By April 1945 the war in Europe was nearing its conclusion, and the general focus shifted to the Pacific theatre. Nieuw Amsterdam embarked a contingent of over 4,000 Australian troops and set sail on the 22nd of the month for the Antipodes. She had passed through the Mediterranean and was entering the Indian Ocean on 8th May when news of the German surrender reached the ship. Having returned via South Africa to Liverpool she took a contingent of Canadian troops home before receiving much needed repairs at Todd’s shipyard in New York. On 24th August the Dutch flagship departed from her Hoboken pier and sailed west, arriving in Southampton for the first time in almost six years on 31st August. Three days later, as she lay at her berth, came news of the Japanese surrender. There was jubilation onboard.

In a reversal of her previous role Nieuw Amsterdam’s subsequent westbound voyages were full of returning Canadian and US troops. Eastbound she carried former Axis POW’s and returning evacuees. On 10th October 1945 Cunard-White Star handed management back to Holland America Line in an emotional ceremony onboard. Over the course of the conflict Nieuw Amsterdam had steamed more than 530,000 miles, carrying 378,361 troops to all major theatres. Although the Cunard Queens were justifiably feted for their wartime role, Nieuw Amsterdam, like the similar sized Mauretania, Ile de France and Aquitania, made an invaluable, if relatively unsung contribution to the Allied victory.

The end of the war did not however signal the end of Nieuw Amsterdam’s troop carrying and humanitarian duties. Like so many colonial powers the Dutch now faced a nascent, frequently hostile, independence movement in its East Indies territory. Nieuw Amsterdam was therefore sent with troop reinforcements, and returned with civilian evacuees from Java, most of whom had also suffered internment during the Japanese occupation. Together with her fleet mate Volendam, also carrying evacuees, Nieuw Amsterdam docked at Southampton at 0930 on 1st January 1946, discharging her passengers before entering the King George V dry dock for remedial work. On 22nd January she departed, now bearing Holland America funnel colours, for Singapore where another contingent of Dutch evacuees from Indonesia were embarked.

She was finally released for conversion back to commercial service on her return to Southampton and slipped away on 9th April, bound for Rotterdam and the emotion charged welcome described at the start of this article. Once those festivities had subsided Nieuw Amsterdam was ushered the short distance to her builders and the start of a fourteen-month transformation.

Following a comprehensive survey and removal of the utilitarian troopship fixtures and fittings, work began on transforming the ship for fare paying passengers. Amongst a plethora of mind-boggling statistics, over 300 miles of wiring, 12,000sq. ft. of glass and 2,700sq. ft. of teak decking was removed and replaced. Acres of wood panelling and handrails were planed down to half their original thickness, to erase thousands of initials and messages scrawled by her wartime clientele. The blistered rubber flooring and 2,200 porthole surrounds were replaced, as was almost all the carpeting. Piping was cleaned or replaced, brass work burnished, and new bathrooms installed. Furniture was returned from San Francisco but in many cases found to have significantly deteriorated over the ensuing years. Despite austerity and the widespread lack of materials and equipment, craftsmen and women across the country laboured to revive over 3,000 chairs, 500 tables and innumerable fittings.

In addition to completing what was considered the most thorough restoration of its type, the opportunity was taken to make certain modifications. Whilst much of the original artwork survived and was refitted, Gerard Roling’s Grand Hall murals were replaced by a balcony cocktail bar at one end and a musician’s gallery at the other. This room also received new chairs, carpets, and curtains. The Cabin Class theatre had proved so popular in her brief pre-war service that another, for Tourist and Third Class passengers, was installed on Lower Promenade Deck. The ship had already proven her cruising credentials and so HAL invested in an outdoor swimming pool on the aft section of Promenade Deck, served by a new adjacent ’Tropical Bar’.

Routine maintenance had been compromised during the hard-pressed war years and so the main and auxiliary machinery were given a much needed, thorough overhaul. The boilers were virtually rebuilt, and propeller blades replaced. Safety was enhanced with the fitting of a comprehensive sprinkler system, whilst a carbon dioxide extinguishing system was installed in the engine room and smoke detectors in the cargo holds.

After a brief trip to Southampton, where eight coats of paint were applied, the pristine Nieuw Amsterdam returned to Rotterdam in late October 1947 and was stored and readied for service. The refurbishment had cost 12 million Guilders, almost as much as the original construction costs, but in return HAL were receiving a virtually new ship. She departed her home port on 29th October 1947, receiving a heartfelt welcome in New York, where fireboat fountains, tugs and sightseeing excursion craft escorted her to the 5th Street Hoboken pier.

Although the ship was still subdivided into three classes, the names were confusingly re-shuffled. Consequently, the pre-war ‘Cabin Class’ designation was dropped for the premium accommodation, which was now called First Class, although the name was re-applied to the former ‘Tourist Class’ (equivalent of Second Class). Completing the confusion, the former Third Class was rebranded as Tourist Class.

Nieuw Amsterdam’s reintroduction coincided with the post-war boom in transatlantic travel. Although robbed of her pre-war consort Statendam, which had been destroyed during the bombing of Rotterdam on 14th May 1940, Nieuw Amsterdam quickly re-established herself as one of the finest and most popular transatlantic liners. She had few comparable competitors in those immediate post-war years, with a ten year moratorium on German flag passenger liner services the only equivalent vessel plying to the heart of Europe was the United States’ line’s America. She thrived. Both Hollywood and ‘real’ Royalty frequently favoured her. Consequently, First Class passengers entering the Grand Hall or Ritz-Carlton Café might rub shoulders with the King of Belgium or the Duke of Gloucester, as well as Spencer Tracy or Rita Hayworth. Dr Albert Schweitzer made a much publicised west-bound crossing onboard Nieuw Amsterdam in June 1949, whilst others, like Cary Grant or Katherine Hepburn, did little to hide their preference and affection for the ship.

Initially she was teamed with the aged Volendam and Veendam. The revised eight day crossing schedule now included calls at Le Havre (rather than Boulogne) and Southampton in both directions. In 1951 and 1952 these veterans were replaced by a pair of similar sized but in their own way radical liners, expressly built for the burgeoning tourist trade. Indeed, with just 39 First Class berths amongst a passenger load of 875, the Ryndam and Maasdam offered a completely different experience to their larger fleet mate, with Tourist Class enjoying the full run of the ships.

Like most liners Nieuw Amsterdam endured her fair share of Atlantic storms. Although she gained a favourable reputation as a solid sea boat, she had to be quickly slowed in head seas, and bridge windows were smashed on one particularly violent early 1950s crossing. Passenger discomfort was partly addressed in late 1956, when Nieuw Amsterdam was fitted with a pair of Denny Brown fin stabilisers during an extensive annual refit. At the same time air conditioning was extended to all areas of the ship, including crew quarters, and externally she returned to service sporting HAL’s new light grey hull livery, which had been introduced on Ryndam and Maasdam. Traditionalists inevitably bemoaned the change, but it gave her a fresh, modern appearance and was said to be cooler for tropical cruising. This latter employment concentrated mainly on the Caribbean but she also sailed farther afield, from New York to the Eastern Mediterranean (the Holy Land, Istanbul and Greek Islands), to the fjords of Norway and even a repeat of her pre-war circumnavigation of South America.

As Nieuw Amsterdam returned to New York in January 1957 and tested the air-conditioning with a series of West Indian cruises, a new fleet mate, the 24,294 Statendam was nearing completion and undertaking trials at the Wilton-Fijenoord shipyard at Schiedam. In effect a larger, faster, and updated version of the Ryndham and Maasdam the new vessel laid a similar emphasis on Tourist Class dominance. In fact, the 84 First Class passengers, 10% of the complement, were confined to accommodation and public rooms at the top of the ship, creating an innovative horizontal class delineation. At 19 knots the new ship’s increased speed made her nominally compatible with Nieuw Amsterdam, but it was not until the end of the decade, some twenty years after her introduction, that the ’Darling of the Dutch’ finally received a worthy running mate.

Built at the same Rotterdam Dry Dock Company facility, Rotterdam steamed into New York harbour in September 1959 to great acclaim. Famed for her novel, slender funnels, her silhouette was certainly radical and distinctive. Inside she provided a broadly even distribution between First Class (655 passengers) and Tourist Class (801), separated along the same egalitarian horizontal delineation as Statendam. At 38,675grt and a service speed of 20.5 knots Rotterdam took over the mantle of company and national flagship, but also helped to fill the void to provide a balanced transatlantic service with Nieuw Amsterdam. The irony of course, was that in the previous year aircraft had finally outstripped ships as the transport of choice for crossing between Europe and the United States.

In October 1961 Nieuw Amsterdam was pulled from the schedules for another major refit, the prime purpose being to convert her into a two-class transatlantic liner and an even more effective cruise ship. The former Cabin and Tourist Class sections of the ship were upgraded and redecorated, with additional en suite facilities installed. She returned to service with a more flexible and contemporary look and feel. Depending on circumstances she could accommodate up to 691 First Class with 581 in Tourist, or alternatively just 301 in First and 972 Tourist Class.

In March 1963 HAL vacated their Hoboken pier and moved to the opposite bank of the Hudson, to downtown New York and a newly leased facility called Pier 40. Formed by the amalgamation of five former finger piers, this 14.5 acre site, the largest on the Hudson, offered three berths and significant car and commercial vehicle parking along with significant office space. It was as she was resting between voyages at one of these piers that an out of control, fully loaded railroad car float, inadvertently rammed her stern, buckling several plates. On 4th January 1965 there was an even more disconcerting encounter with the same kind of vessel. This time she was in-bound, passing through pre-dawn mist a mile from the Verrazano Narrows Bridge when she rammed an unlit, unmanned car float. Five railway wagons were jettisoned into the sea, whilst the ship suffered a gash in her starboard bow, fortunately 10ft above the waterline. She proceeded to Pier 40 where inspectors and divers confirmed there was no significant damage. The gash was duly patched, and she sailed on her next cruise without disruption.

Whilst contemporaries like America and Mauretania were sold off or scrapped, Nieuw Amsterdam remained a prominent fixture of HAL’s plans throughout the early and mid-1960s. In 1967 however it seemed time had finally caught up with ‘Darling of the Dutch’. It started in April when one of the boilers malfunctioned. The additional demands on the remaining boilers caused collateral problems and cracked tubes, which no amount of patching up could resolve. Two transatlantic crossings had to be cancelled, together with a cruise to equatorial Africa. Fortunately for the ship most of the company board were in favour of saving her, even if others considered selling her for scrap. It was uneconomic to commission new replacement boilers, but a fortuitous solution emerged from a most unlikely source.

Analogies with human organ transplants are inevitable and in this case the donor was a superannuated US Navy cruiser. Like so many vessels of her type, expediently built in 1944 to win a war that was soon concluded, she had lain dormant for almost two decades before being sold for scrap. HAL hurriedly purchased two of the boilers, together with three identical ones held in storage by the US Navy. They were loaded onto a company freighter, Moerdyke, which brought them back from California to Wilton-Fijenoord.

In the interim Nieuw Amsterdam had been manoeuvred into the yard’s dry dock, where a 33ft x 23ft incision was made in each side of the hull. By means of greased rods, girders and pulleys, five of the original six boilers were slowly and meticulously extracted from the ship, before being hoisted clear by the yard’s huge gantry crane. Two of the new boilers were then slotted into the portside void, alongside the one superfluous original that was retained as ballast. The process was repeated on the starboard side, where the remaining three US Navy replacements were installed.

Once the new boilers had been hooked up, fired up and tested, and the gaping holes in her flanks were resealed, Nieuw Amsterdam set out for further trials in the North Sea, on 30th November 1967. These proved more than satisfactory. Although less powerful than the originals (she now had only five rather than six) the new boilers were smaller, lighter and considerably more efficient and economical, whilst still permitting a service speed of 19.5 knots.

Rejuvenated, the Nieuw Amsterdam sailed into the new decade as the last of a vanishing breed of inter-war liners, favoured by those who preferred her ’classic’ style and status over the shiny new, space age competition. Nevertheless, even the new generation of ships were fighting a losing battle against the jets, their task became almost impossible with the advent of the Boeing 747 ’Jumbo’, which offered cheap and fast intercontinental travel to the masses. With her crew regularly out-numbering passengers, even on summer ‘high season’ crossings, it was simply a question of time. HAL finally decided to terminate their transatlantic service in 1971. By then Nieuw Amsterdam was already spending more time cruising, but appropriately and symbolically she was selected to make the company’s final scheduled sailing from Rotterdam, on 8th November 1971.

HAL now shifted operations entirely to cruising. In September 1972, to reduce costs in a fleet wide restructuring, ownership of the ship was transferred to a single purpose company, NV Nieuw Amsterdam, with the port of registry shifting to Willemstad, Curaçao in the Dutch Antilles. Equally unpopular amongst her many devotees was a wholesale influx of Indonesian crew members, cheap labour replacing many of the Dutch staff.

Despite these changes Nieuw Amsterdam retained a loyal following. As a brochure proudly boasted, she was not only the largest cruise ship sailing year-round from Florida, she was also the grandest one afloat. Initially there were a series of fourteen night cruises from Port Everglades to the Caribbean. Later, from October 1972 to May 1973 an abridged ten day itinerary was implemented. Until December these sailed to Willemstad (Curaçao), La Guiara and Pampatar (Venezuala), Fort-de-France (Martinique) and Charlotte Amalie (St. Thomas). From 19th December, St Georges (Grenada) and Basse-Terre/Pointe-à-Pitre (Guadeloupe) replaced the Pampatar and Fort-de-France calls. With fares ranging from $280 to $1,050 per person, depending on sailing and accommodation, she could cater for all budgets. One change that thankfully escaped Nieuw Amsterdam was a new corporate livery, introduced on the Statendam in 1972. Although traditionalists might have welcomed the dark blue hull, everyone it seems was grateful that the new red, white and blue funnel colours were never applied to those shapely stacks.

In early 1973 HAL was restyled as Holland America Cruises (HAC) and the company introduced three new vessels. Moore McCormack’s Argentina and Brazil, which had been acquired the previous year, emerged after comprehensive refits as the cruise ships Veendam and Volendam to be joined by Prinsendam, the company’s first purpose built cruise ship. With her disproportionately high wage bill and thirsty turbine machinery Nieuw Amsterdam’s position was already tenuous. Then came the OPEC oil crisis of October 1973.

With the cost of fuel quadrupling overnight and a reported $12.5 million loss on its passenger ship operations, HAC was forced to act. There could be no room for sentiment, so having steamed into Fort Lauderdale on the morning of 17th December 1973 and offloaded her passengers and their luggage Nieuw Amsterdam sailed to an offshore anchorage, whilst her fate was considered. A number of proposals were made to keep her in a static role, ranging from an exclusive five star hotel, to a rather less salubrious brothel. Holland America considered them all but, in the end, sold her for 13 million guilders to the Nan Feng scrap yard of Kaohsuing, Taiwan.

With a skeleton crew of sixty under the command of Captain R. Ten Kate, Nieuw Amsterdam weighed anchor early in 1974 and made for Curaçao, on the initial leg of her delivery voyage. The price of fuel was not the only consideration, there was also the issue of availability. With OPEC slashing production (hence the inflated price), Bunker C oil was also in short supply. After tense negotiations the chief engineer secured sufficient for a transit of the Panama Canal and more was acquired in Los Angeles, for the journey across the Pacific. Nevertheless, to eke out the dwindling supply the great ship idled along at a sedentary 12 knots.

Nieuw Amsterdam was greeted by a tropical downpour when she arrived off Kaohsuing on 25th February 1974. Six days later, on Saturday 2nd March, she was manoeuvred to breaking berth 57. Captain Kate was reported to be furious when the docking pilot unceremoniously scraped the great ship along the flank of Home Line’s Homeric, also awaiting demolition. Alas by then it was irrelevant. Stripped of her fixtures and fittings, the process of cutting her up started from the stern in mid-May, thirty six years to the day after her triumphant maiden arrival at Hoboken. The final bow plates were removed for recycling in early October, bringing the curtain down on one of the most famous and beloved transatlantic liners of all time.

Comments

Sorry, comments are closed for this item