Immigrant Ship and Trooper

This famous twin funnelled troopship is well remembered for her voyage from the Caribbean to Tilbury in June 1948 with 492 immigrants, plus several stowaways, who were seeking work in London as the first post war Caribbean immigrants. The massive movement of immigration into Britain over the last seventy years has seen the word ‘Windrush’ enter the English language as an example of the new multi-cultural society and citizenship of Britain and what it today means to be ‘British’. In 1998, an area of public open space in Brixton, London, was renamed Windrush Square to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the arrival of the Empire Windrush’s West Indian passengers. Ten years later, a blue Thurrock Heritage plaque was unveiled at the London Cruise Terminal in Tilbury, and in 2018 we celebrate the 70th anniversary of her arrival with British Caribbean immigrants as an established and familiar part of the British way of life.

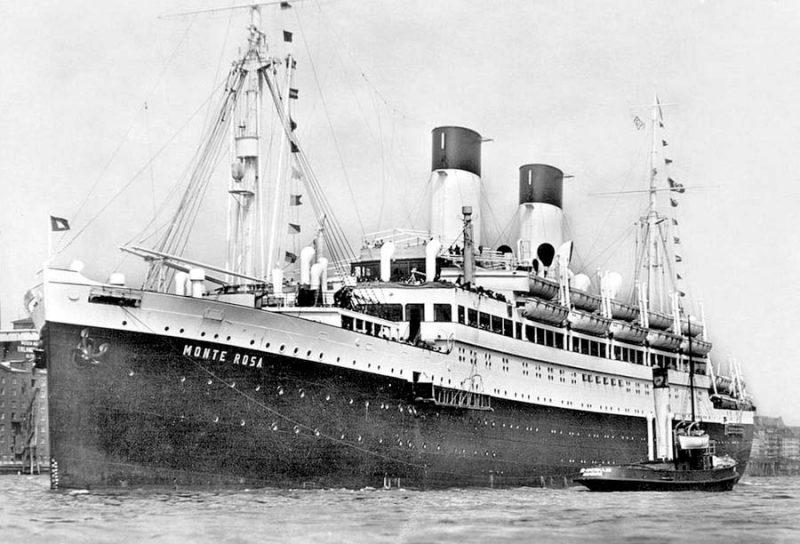

Monte Rosa

Empire Windrush started life a world away from this as the last of a quintet of ‘Monte’ passenger and cruise ships for the Hamburg Süd America Line, formed in 1871 and the most famous of the European shipping lines serving South America. Monte Rosa of 13,882 grt wore the white funnels and red tops of Hamburg Sud and a proud red and white quartered houseflag flying from her foremast with the letters ‘H S D G’ in black in the quarters. Monte Rosa was launched on 4th December 1930 as Yard number 492 at the famous Hamburg shipyard of Blohm & Voss, which had also completed her four earlier sisters Monte Olivia (1924), Monte Sarmiento (1925), Monte Cervantes (1927), Monte Pascoal (1930), and with Monte Rosa completed in 1931.

Monte Rosa had dimensions of length 500.3 feet (152.48 metres), moulded beam of 65.7 feet (19.99 metres), depth of 37.8 feet (11.48 metres) and loaded draft of 26.7 feet. She had five continuous decks in her hull including the uppermost continuous deck (‘C’ Deck), and above that were the passenger accommodation and public rooms of Promenade Deck (‘B’ Deck), Boat Deck (‘A’ Deck) and the Navigating Bridge Deck in her ‘midships accommodation of length 299.0 feet. The quintet of ‘Monte’ passenger liners were diesel powered by a quartet of M.A.N. six cylinder four stroke single acting diesel engines single reduction geared to twin screw shafts by the shipbuilder, each of 6,800 bhp and a total of 27,200 bhp, to give a service speed of 14.5 knots. This speed was considered adequate for the South American service and for cruising, but was only half of the speed of the express steam turbine powered liners employed on the busy North Atlantic route. The steam powered auxiliary deck equipment used steam raised from twin cylindrical Scotch type boilers in the boiler room.

Monte Rosa had accommodation for 2,408 passengers, with half of this number in Second Class in the better staterooms of the ‘midships accommodation, and half in the lower decks for Third Class, which in fact was dormitory accommodation for steerage passengers. She had two sets of Dining Rooms and Main Lounges and smaller public rooms, with the Second Class of course being a lot grander and with the addition of a Verandah Cafe at the aft end of Promenade Deck. The public rooms and Second Class staterooms were beautifully panelled in various woods on top of two inches of fireproof material. She carried a crew of 253, and had cargo space in her holds for 406,000 cubic feet of dry cargo, and 5,600 cubic feet of refrigerated cargo, to give a deadweight tonnage of 10,896 tonnes.

The hull of Monte Rosa had eight watertight bulkheads extending to ‘D’ Deck, with the collision bulkhead reaching up a deck higher than the others. She had a foremast, mainmast and cruiser stern with several derricks on each mast and sets of posts, 28 lifeboats in total in banked pairs, and her navigating bridge had the latest of navigation equipment including wireless direction finders and submarine signalling apparatus, with every deck and the whole accommodation and public rooms lit by electricity. The engine room had four power operated watertight doors, with one between the engine room and boiler room, another at the steering flat entrance to the shaft tunnels, and one each at the forward entrance to the shaft tunnels. These were operated by hydraulic and pneumatic power, employing an accumulator tank filled with air and water situated in the engine room and working at a pressure of 400 pounds per square inch.

There were a total of thirty fireproof doors in the corridors of ‘E’ Deck, ‘D’ Deck, ‘C’ Deck, ‘B’ Deck and ‘A’ Deck, and a total of 55 ventilation supply fans and 24 exhaust fans and one combined supply/exhaust fan situated throughout the ship. There were 94 portable fire extinguishers for use in the passenger accommodation, and 14 more in the machinery spaces in addition to the usual powerful fire pumps. Monte Rosa had three generator sets of 350 kilowatts driven by internal combustion engines of the trunk piston type arranged along the starboard side of the engine room, with an additional generator later added to increase the electrical power capacity.

The immigration trade to South America failed to live up to expectations, and thus the Hamburg Sud quintet went cruising at more modest prices then the bigger established cruise lines. Monte Cervantes sank near Tierra del Fuego while on a cruise in 1930, but the remaining members of the class operated throughout the 1930s on the immigrant service to South America, as cruise ships, and as part of the ‘Strength through Joy’ German programme of the mid 1930s, which provided leisure activities and cheap holidays as a means of promoting the ideology of the Third Reich. Monte Rosa ran aground while on a cruise on 23rd July 1934 off Thorshavn in the Faroe Islands, but came off undamaged the following day. Monte Rosa sailed with her sisters on the outward voyages from Hamburg calling at Vigo and Las Palmas to Rio de Janeiro, Santos, Sao Francisco de Sul, Rio Grande, Montevideo and Buenos Aires. The return voyages called at all of these ports to arrive back at Hamburg after a three month voyage.

Monte Rosa had a busy career during World War II in a military role, starting as a barracks ship at Stettin, then as a troopship for the invasion of Norway in April 1940. In November 1942, she was one of several German passenger ships used for the deportation of Jewish Norwegian people. Monte Rosa carried 46 people from Norway to Denmark including prominent businessmen, writers and artists, all of which were transferred to trains bound for the ‘death camp’ of Auchswitz, and unfortunately only two were found alive when the camp was liberated in 1945. She was later much used as an accommodation repair ship and recreational ship attached to the battleship Tirpitz stationed in Altenfjord in northern Norway, along with the battlecruisers Gneisenau and Schaarnhorst, which made regular forays into the Norwegian Sea to attack Allied convoys making for Murmansk with munitions. Monte Rosa was damaged by British Bristol Beaufighter aircraft in her camouflaged lair near the Tirpitz at the end of March 1944, and three months later Norwegian Resistance Movement fighters attached limpet mines to her hull, but although damaged she did not sink from either attack. She was released from her duties in Northern Norway, and became a troopship and hospital ship in the Baltic later in 1944 to take part in the rescue attempts of Germans along the Baltic coast from Latvia, East Prussia and Danzig fleeing from advancing Russian troops. On 16th February 1945, she struck a mine off Hela Spit and was towed to Gdynia and temporarily repaired. She was then towed to Copenhagen with 5,600 refugees, wounded and sick onboard, arriving with her lower decks under water and slowly sinking. She became a hospital ship, and again survived this dangerous mission as many of her fellow German liners were sunk with huge loss of life by Russian submarines.

Monte Rosa was captured by advancing British forces in May 1945 at Kiel and taken as a prize for war reparations by the British Government. She was relatively undamaged and towed to a berth where she was inspected for her damage on 23rd June 1945. She was in fact the only survivor of her class at the end of World War II, and although with a flooded engine room, she was considered worthy of repair and was sent to the United Kingdom for an extensive refit and conversion to a trooper and managed by the New Zealand Shipping Co. Ltd. She was then assigned to the Ministry of Transport as a troopship after her arrival on the Tyne at Jarrow in August 1945. Seven months later she was repainted in British troopship colours but still retained her German name. She sailed in June 1946 to the Clyde yard of Alexander Stephen and Sons Ltd. for a nine month refit to restore her to full troopship condition.

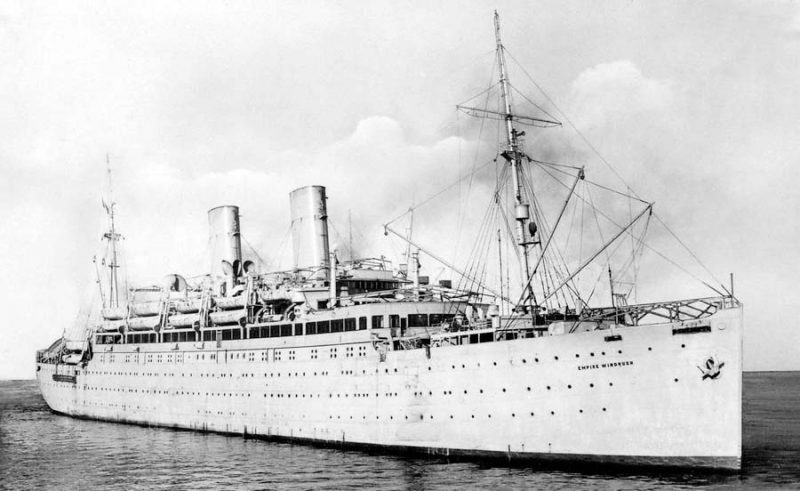

Empire Windrush

Monte Rosa was renamed Empire Windrush on 21st January 1947 after the minor Windrush tributary of the river Thames flowing from the Cotswolds at Newbridge in Oxfordshire, the bridge over the Thames having been built around 1216 by monks. She was to be used on the regular trooping service from Southampton to Gibraltar, Suez Canal, Aden, Colombo, Singapore and Hong Kong route with voyages extended to Kure after the start of the Korean War in 1950. She made 13 round voyages with troops to the Far East, 4 to India, 1 to Australia and the West Indies and 10 to the Mediterranean, 28 voyages in all.

The main diesel engines of Empire Windrush were given a thorough overhaul during a four month refit at Southampton from April 1950, during which the blast fuel injection system was changed to solid fuel injection. Fourteen fire alarms were also fitted throughout the ship during this refit. Due to her augmented safety equipment, Empire Windrush had a Class I Passenger and Safety Certificate throughout her years as a troopship. She now had 22 lifeboats on Boat Deck with 20 of these double banked for a maximum passenger capacity of 1,571, together with 1,980 liferafts, and a gross tonnage of 14,691 tonnes.

She was one of over a dozen ‘EMPIRE’ troopships working alongside her in post-war years for the Ministry of Transport, most with names with suffixes named after rivers, and in addition to the long term chartered British India Line and Bibby Line dedicated troopships. The ‘EMPIRE’ troopships were managed by Anchor Line, British India Line, Bibby Line, Orient Line, P. & O. Steam Navigation, Lamport and Holt, Prince Line, Donaldson Brothers and Black, Royal Mail Line and Chandris (England), and were as follows:

| Name | Previous Name | Grt | Year | Builder |

| EMPIRE BRENT | Ex Letitia | 13,595 | 1925 | Fairfield |

| EMPIRE BURE | Ex Elisabethville | 8,392 | 1921 | Cockerill |

| EMPIRE CLYDE | Ex Cameronia | 16,584 | 1920 | Beardmore |

| EMPIRE FOWEY | Ex Potsdam | 19,121 | 1935 | Blohm & Voss |

| EMPIRE HALLADALE | Ex Antonio Delfino | 14,056 | 1921 | Vulkan Werft |

| EMPIRE HELFORD | Ex Czaritza | 6,852 | 1915 | Barclay, Curle |

| EMPIRE KEN | Ex Ubena | 9,523 | 1928 | Blohm & Voss |

| EMPIRE MEDWAY | Ex Eastern Prince | 10,926 | 1929 | Napier & Miller |

| EMPIRE ORWELL | Ex Pretoria | 18,026 | 1936 | Blohm & Voss |

| EMPIRE PRIDE | Built as a trooper | 9,248 | 1941 | Barclay, Curle |

| EMPIRE TEST | Ex Thysville | 8,298 | 1922 | Cockerill |

| EMPIRE TROOPER | Ex Cap Norte | 14,106 | 1922 | Vulkan Werft |

Empire Windrush embarked contingents of many British Regiments in her career as a troopship, with the Gloucester Regiment, 8th King’s Royal Hussars, Durham Light Infantry (DLI) and the Royal engineers embarked at Southampton in October 1950 for Korean ports as part of the United Nations Forces preventing the seizure of South Korea by Communist forces operating in the northern part of Korea. Empire Windrush caught fire in May 1949 in the Mediterranean while she was on passage from Gibraltar to Port Said, and four British naval ships were put on standby to assist or tow the ship to port if necessary. The troops and passengers were put into the lifeboats as a precaution, but the boats were not launched and she was towed back to Gibraltar. Another fire broke out shortly after she sailed from Hong Kong on another homeward voyage when the number four generator exploded into flames.

Carribean Immigrant Voyage

Empire Windrush made a voyage in 1948 under Capt. John Graham Almond to Australia and returned via the South Atlantic to the West Indies to pick up some Caribbean troops who were on leave from their regiments. The British Nationality Act of 1948 had just been passed, giving the status of citizenship to all British subjects living in the colonies. She called first at Trinidad, then at Kingston in Jamaica, next at Tampico in Mexico, followed by Havana and Bermuda, with the ship carrying predominantly Jamaican, Trinidadian and Bermudan people. The ship, however, was not full of troops, and an advertisement had been placed in the Jamaican Gleaner for anybody who wanted to come and work in the U.K. The advertisement of Tuesday 13th April read ‘Passenger Opportunity to the U.K. on a troopship sailing in May 1948, applicants must have the £28.50 fare plus £5 in cash when they sail’.

Many poor Jamaicans could not afford this fare, but former West Indian Regiment servicemen took this opportunity to return to the U.K. with hopes of rejoining the forces, with others wanting some form of employment after being unemployed for three years in the drastically impoverished post-war economy of Jamaica and the disastrous aftermath of a massive hurricane in 1944. Empire Windrush sailed from Kingston on 27th May 1948 (Empire Day) for Tilbury, arriving on the Thames on 22nd June 1948 with 492 immigrants and a number of stowaways.

Some of the stowaways had their fare paid by ‘whiprounds’ of the other passengers after being found hidden in remote corners of the ship. The new arrivals counted many former Army servicemen and officers, builders, nurses, cooks, newspaper workers, hairdressers, plumbers, painters, shipwrights, locksmiths, carpenters, boxers, welders, farm workers, mechanics, tailors, calypso singers and musicians including a complete steel drum dance band among their number. They mostly had skills which could convert them into useful citizens if they stayed long enough and if they could put up with the large amount of discrimination that they all found from every section of British society. Many of the pre-arranged forwarding addresses were in London, but others were spread out over the country from Edinburgh to Bristol.

There was a warm welcome at Tilbury from the officials of the British Immigration Service including Ivor Cummings of the Colonial Office welfare department, but the country was unprepared to accept them as there were only five families among the immigrants, the remainder being single men. The stowaways were sent to Grays Magistrate Court and given minimal token fines, however one stowaway had no identification papers whatsoever and was deported back to Jamaica. The five families and some of the single men were soon on their way by train to their pre-arranged addresses, while the remainder were given temporary accommodation in Clapham Deep Shelter on the Northern Underground line. This was in South West London, and the unemployed were told to report to the Brixton Employment Exchange a mile away to begin their search for employment.

However, white landlords refused to accept the immigrants on the basis of their colour, and it took the power of the trades unions, local councils, professional and staff associations and most importantly the various religious denominations to change this unacceptable face of racist British society. The Notting Hill Carnival in North London became a familiar and established carnival with coloured people very visible in the street festival, in the same streets where they had once found serious racial violence from gangs of white racist youths. The Windrush immigrants were the first landmark wave of people into an area that now has thirty different nationalities living peacefully amongst the local indigenous population. Central to this success in Notting Hill was the setting up of language translation and history groups, one for each nationality or racial grouping, which translated the local history of this area into their many languages while at the same time encouraging the attendance at English language classes to properly assimilate the immigrants into society.

During the 1950s, as labour shortages continued in Britain, migrants from Jamaica continued to arrive at a steady rate, with 191,330 Jamaicans arriving to settle between 1955 and 1968. In total, nearly one half a million coloured people left their homes in the West Indies to come and work in Britain in all manner of jobs. There were extreme outbreaks of violence in 1958 in areas of London and Nottingham where West Indians lived, and the shock of the treatment meted out by racist white youths was so bad that many returned home immediately to the Caribbean. They were some of the most enterprising and hard working members of their communities, and their departure from the Caribbean had deprived their homeland of important skills, which returned with them to set up useful and successful businesses. Britain, it is true, had found it hard to absorb them, and the white population resented the Caribbean peoples taking some of their jobs, but the economy of Britain could have risen to a level with them that resulted in the highest contribution per head to the national income. The racial, political and social problems of their absorption unfortunately became too great, and many coloured people returned home greatly disillusioned.

British Racial Discrimination

The Empire Windrush passengers arrived with a naive perception of the ‘Mother’ country and were ill prepared to deal with the hostility and resentment of most British people, even though they held British passports and were thus ‘British’ in law by the British Nationality Act of 1948. The police service consisted of white officers drawn from British communities and could do little to help the immigrants when they turned to the police after suffering violence and abuse on the street and in the workplace. They often could not open a bank account or secure a loan or a mortgage, and instead they joined together in a co-operative movement of saving money to buy homes, and established their own organisations such as the West Indian Standing Conference to represent their interests in the predominantly white society. The arrival of the Empire Windrush was a turning point in British history and has come to symbolise their fight for racial equality while changing the traditional attitudes of British people and life.

All of the Empire Windrush passengers in fact quickly found work, as there was a post-war scarcity of labour. One month later, they were at work as trainee nurses, bus and train drivers and bus conductors, clerks, Post Office workers, coach builders, plumbers and fitting out trades, foundry workers, railway workers, labourers, farm workers, electricians and many other occupations. They made a great contribution to the rebuilding and rejuvenation of British cities after their destruction at the hands of German bombers.

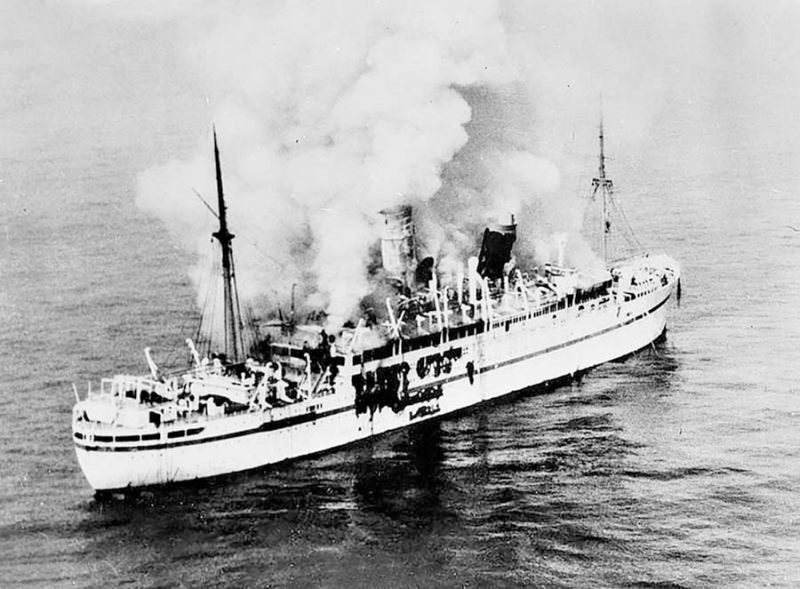

Final Fateful Voyage

However, Empire Windrush was only to continue in this role of troopship for a total of eight years as she sank on 29th March 1954 off North Africa on her 29th trooping voyage after an engine room fire and explosion killed four engineers when she was off Algiers. She was bound to Tilbury from Japan and her troops, passengers and remaining crew were taken off, with the Royal Navy frigate Enard Bay and destroyer Saintes making valiant but unsuccessful attempts to tow her into Gibraltar. She had sailed from Yokohama in early February 1954 and then from Kure on 19th February, and then called at Hong Kong and Singapore. The troops included a contingent of the Duke of Wellington’s Regiment and the Durham Light Infantry (DLI), many wounded at the Third Battle of the Hook in May 1953, and also military families were onboard. Empire Windrush had many defects during the first part of this very slow voyage, with the forward compressor exploding on 8th March, and it seemed the voyage would end at Colombo and she would be laid up. Capt. Wilson and Chief Engineer Christian discussed the many problems at length in Colombo, but decided to continue the voyage despite the parlous state of her engines and her almost unsafe, unseaworthy condition.

The ship had failed to maintain her prearranged schedule on many occasions during the two years before her final fateful voyage and loss, with her overworked engineers having to repair her main engines and auxiliaries at foreign ports outside of the U.K. She reached Port Said at slow speed after eight weeks of the voyage with 1,276 troops, women and children onboard, but several of the single men walked off the ship and refused to travel any further in her. Fortunately, their gear and possessions were taken off the ship, as all other survivors of the Empire Windrush lost everything in their luggage when she sank to the bottom of the Mediterranean.

At 0617 hours on the morning of 28th March 1954 when the troopship was thirty miles north of Cape Caxine in Algeria, the Master and Chief Officer heard a loud thud with immediate black smoke and orange flames coming out of the aft funnel. This was caused by a large fall of soot from the inside of this funnel landing on the starboard side of the engine room and rupturing her fuel lines to the main engines. A glowing mass of incandescent soot was the heat source to ignite the oil fuel in quantity. The Chief Officer led a firefighting team to the aft lower decks and found that the double door on ‘E’ deck to the engine room was already very hot with bright orange flames and much smoke issuing from the sides of the door. Water hoses were put into operation but the supply of water failed within minutes due to a cut-out of electrical power, particularly from the troublesome emergency power supply, and firefighting efforts were discontinued. Unfortunately, four engine room personnel had died in the blast, these being Third Engineer G. Stockwell, the Seventh Engineer, Eighth Engineer Leslie Pendleton aged 21 years of Bootle, and an electrician. These four men were probably together in the Engineer’s Store and became trapped by the fire.

One greaser in the Engine Room and another greaser in the Boiler Room were the only survivors of the six personnel in the two engine compartments at the time of the explosion. Capt. Wilson sent out an urgent SOS at 0623 hours, with orders given at 0645 hours to embark the passengers in lifeboats, all of the women and children being taken off in the lower tier of double banked boats. However, power on the winches for the second tier of boats failed and these were then tumbled into the water together with many liferafts and buoyant apparatus. Everything that would float was thrown overboard to assist the many troops that scrambled down rope ladders, and ropes, or simply jumped overboard into the sea. The smoke and flames reached high above the ‘midships of the ship to a height of two or three hundred feet, and were visible from long distances away.

Four rescue ships came to her immediate assistance, in the shape of cargo-liners Socotra, Blue Funnel Line ‘Victory’ ship Mentor, Hemsefjell and Taigete, which raced to her last position at 37° 05′ North, 2° 02′ East. The four rescue ships took all of the survivors into the Port of Algiers, and two Royal Naval vessels were quickly on the scene from Gibraltar and the Western Mediterranean sea area. The destroyer Saintes began towing the casualty at 0945 hours on the following day of 29th March at a speed of 3.5 knots for Gibraltar, but it was to no avail for she sank stern first at 0300 hours on 30th March 1954. The aircraft carrier Triumph was sent from Gibraltar to Algiers to repatriate all of the troops, passengers and crew. Two personnel were later awarded the M.B.E. for their efforts, Lt. Colonel Geoffrey Dockerill helped the troops off the ship until the last man was evacuated, and Radio Officer Francis William Fowler received the award for staying with Capt. Wilson until the end when they abandoned ship together.

The subsequent Court of Enquiry into the loss of the ship concluded that no one was to blame for the tragedy. The Court did however make three important recommendations:-

- Alteration to be made in the requirements for firefighting appliances with a considerable increase in the numbers of smoke helmets supplied to the firefighting teams.

- Periodic inspections to be made to the engine room uptakes and funnels of all vessels

- The location of emergency controls and connections to be clearly displayed on the navigating bridges of all vessels.

Postscript

The swansong of the ‘Empire’ troopships with their white hulls and blue ‘trooping’ band came during the debacle of the Suez Canal crisis in 1956 after President Nasser of Egypt nationalised it. The British and French intervention on 5th November 1956 followed an Israeli attack on Egypt, which was later revealed to have been planned in collusion with the British and French governments. Empire Orwell then brought home the 1st Queen’s Regiment home from Singapore via the Cape during March and April of 1957 after their three year tour of Malaya. She was laid up at Portland in 1958, and the careers of all of the other long distance ‘Empire’ troopers had also come to an end, with only the new troopships Nevasa of 1956 and Oxfordshire of 1957 employed on deep sea trooping.

Nevasa and Oxfordshire had very short British trooping careers of only six and five years respectively, as a White Paper published in 1957 forecast the end of their use, as the first of the Bristol Britannia aircraft of the R.A.F. Transport Command came into service in 1958 able to carry 110 troops over a range of five thousand miles at a maximum speed of 400 mph in very good comfort. They were also considerably cheaper to operate than a fleet of troopships, and thus it was a ‘no contest’ between air and sea trooping. The long, hot voyages of Empire Windrush to distant garrisons had come to an end, and the year 1962 saw the finale of three hundred years of sea trooping for all of the very many regiments of the regular British Army. Empire Windrush was the most famous of the ‘Empire’ troopships and has an immortal place in British maritime and multi-cultural history.

Comments

Sorry, comments are closed for this item