In 1902 the Adelaide Steamship Company ordered two ships to be built by Armstrong Whitworth & Co. on the Tyne, at a cost of about £102,000 each. They would be almost twice the size of any previous ship owned by the company, incorporate all the latest improvements, and provide superb accommodation for 240 passengers.

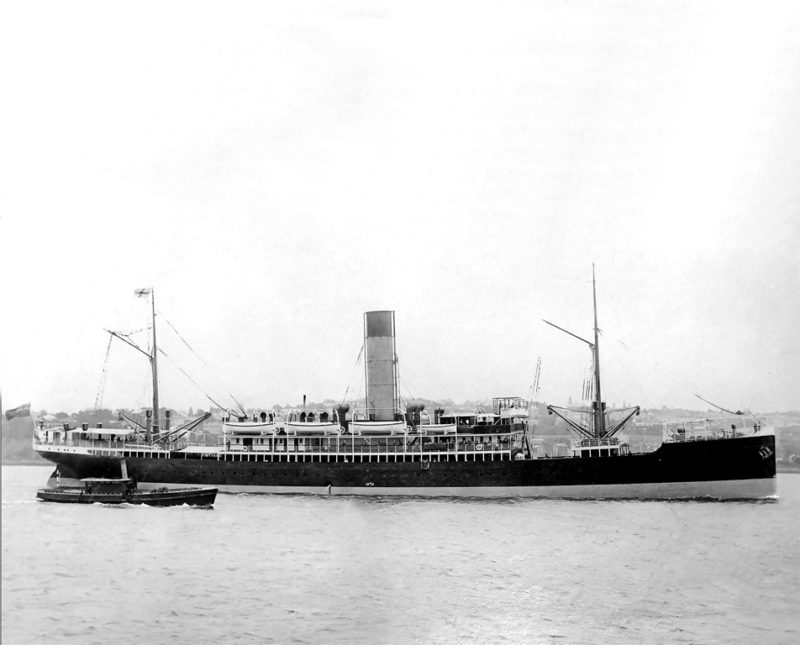

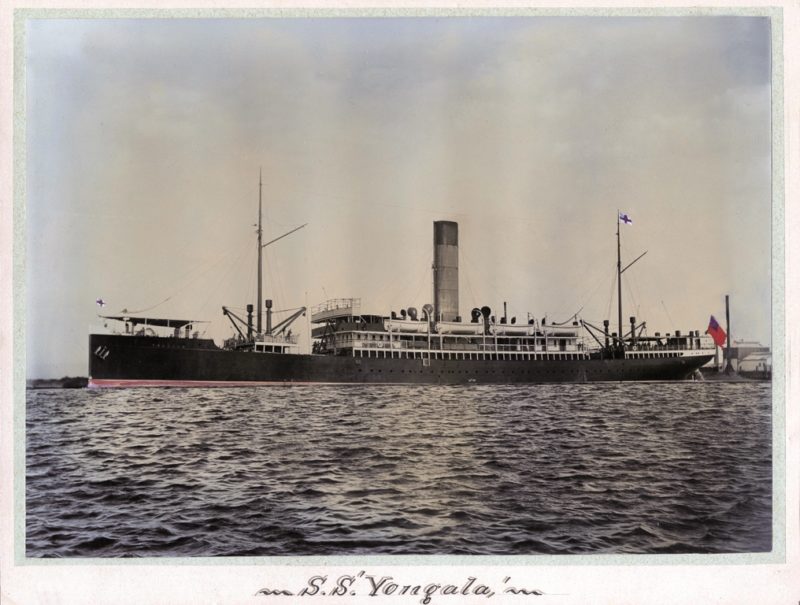

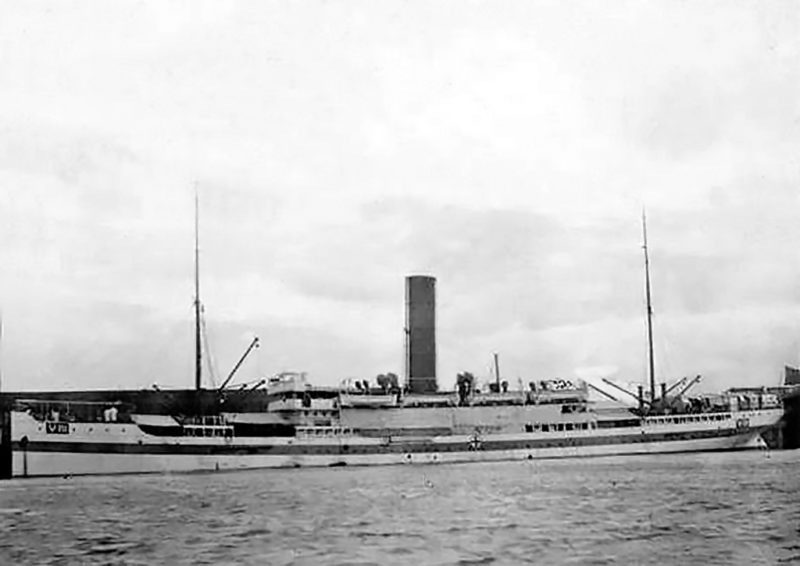

The first vessel was launched on 29th April 1903 and named Yongala, the name of a small town in South Australia and an aboriginal word for a watering place. Trials commenced on 30th September, with a maximum speed of 15.8 knots being achieved, well in advance of the contract speed of 14.5 knots. As completed, Yongala was 3,664 grt, 363 feet long with a beam of 45 feet, and could accommodate 110 first class and 130 second class passengers.

For its delivery voyage to Australia, Yongala was chartered by the Union-Castle Line to carry passengers to South Africa, departing Southampton on 9th October 1903 under the command of Captain J. Sim. After calling at Las Palmas to take on bunkers, Yongala arrived in Capetown on 2nd Novem-ber, leaving on 9th November to continue to Durban. After disembarking all the passengers bound for South Africa, a number of Australians were embarked to be taken home.

Yongala arrived at Fremantle on 23rd November, spending three days in port before departing for Adelaide fifteen minutes after the 6,077 grt Orizaba, operating for the Orient Line, also left for Adelaide. It was generally believed the ships would engage in a race across the Great Australian Bight, and although this was denied by the owners of both ships, when Yongala reached Adelaide on 30th November several hours ahead of Orizaba that fact was widely reported. Yongala went on to Melbourne, arriving on 3rd December, and berthed in Sydney on 6th December, spending the next four weeks there being prepared for the coastal service.

The arrival of Yongala in Australia attracted considerable attention, and a description of the ship that appeared in numerous newspapers included the following:-

She has a poop, forecastle, and long citadel house amidships, and an island deck is arranged in way of the foremast. The deck above the citadel house is carried out to the ship’s side, and forms a spacious and airy promenade, on which is placed a tier of deckhouses, containing drawing-room, saloon, entrance, staterooms, and smoking-room. Above this again is the boat deck, upon which are placed the captain’s room and chartroom, wheelhouse, with living bridge above.

Entering from the promenade deck large doors’ give access to an entrance lobby, from which folding doors open into the drawing-room, and a wide staircase leads down to the dining saloon. The staircase is further continued into a large space below the saloon which has been arranged as a dining-room for children. This room is surrounded by first-class staterooms, and two passages leading aft on either side of the machinery casing give access to the whole range of passenger accommodation, which occupies the full length of the ‘tween deck to the stern.

As the climate in which the vessel is to trade is hot, special attention has been paid to the ventilation, not only in the staterooms themselves, but all the passages and alleyways into which they open, and powerful electric fans are fitted in the engine room, and air trunks are led to all the living spaces.

In the ‘tween decks the passages terminate at their after end in a hall, from which a staircase gives access to the second-class drawing and dining saloons. These rooms are fitted in teak and mahogany respectively, the upper panelling being enamelled white in each case. The drawing-room contains a Broadwood piano. Divisions are arranged in these passages so that a larger or smaller number of staterooms can be used as second-class as may be required, and the doors are arranged so that the second-class rooms may be completely shut off from the first-class! The promenade-deck is exceptionally roomy, and provides well sheltered seating accommodation, which will no doubt be found acceptable by the passengers. Special staterooms are arranged round the engine hatch on the promenade deck, and at the after end there is a large smoking-room, with bar and lavatory openings off it

The first-class passengers have direct access to the upper and promenade decks either through the saloon entrance or by a stairway immediately abaft the funnel, through which entrance the stewards can pass to the staterooms without going through the saloons. The poop deck is allotted to second class passengers as a promenade.

The forecastle deck, island deck, promenade deck, poop and upper decks are all laid in specially selected teak, and the captain’s room, charthouse, and wheelhouse are built of the same material. The galley and pantry accommodation has been very carefully designed, so as to interfere in no way with the comfort of the passengers, and to prevent any smell of cooking reaching the saloons and staterooms.

The first class lavatory accommodation is on an ample and luxurious scale, the bathrooms and lavatories being fitted up in the best and latest style. Spray baths, shower baths, and needle baths are provided, and hot or cold water is, of course, available at any time.

The first-class staterooms are fitted with Messrs Hoskin’s latest design of spring berth, which has been arranged to fold up against the bulkhead when not in use, and thus practically leave the whole of the space in the stateroom free. The soft berths are of Markham & Davies’ patent, the feature of this patent being that the sleeping berths can be immediately converted to day use without the removal of the bedding. The vessel is lighted throughout by electricity. The design of the fittings, lamps, and, their arrangement’s throughout the vessel has been made the subject of careful consideration, and the effect is eminently pleasing.

The walls of the drawing-room are panelled in polished walnut, elaborately moulded and carved, having inlaid panels of decorated anaglypta. Comfortable easy chairs and tea table are provided, whilst round the well an upholstered lounge has been fitted with spring stuffed cushions, covered in silk tapestry (similar to the sofas along each side of room), the back of the lounge being panelled to form a well for light and ventilation to the dining saloon underneath.

The entrance hall from the promenade deck is treated in teak panelling, both to withstand the alternative exposure to heat and damp, and is divided from the companion proper by carved pilasters. The dining saloon is similar in style of design to the drawing-room, but is more elaborate in its detail, and executed in oak stained light brown and waxed polished.

The smoking-room is in some respect the most original in treatment, the departure being in the hand-hammered panels in copper. These panels represent the twelve signs of the Zodiac. The flooring is of india rubber tiling, and the spring seats and backs are upholstered in green pegamoid.

The propelling machinery consists of a set of triple expansion engines built by the Wallsend Slipway and Engineering Company. The cylinders are 32in, 51in and 84in. respectively, with a stroke of 54 in. Both the high and intermediate slide valve are of the piston type, whilst the low pressure engine is fitted with a double ported flat faced valve.

When the two ships had been under construction it was generally expected they would be placed on the east coast trade between Melbourne and Cairns, but during December it was advertised that Yongala would depart Sydney on 2nd January on its maiden commercial voyage to Melbourne, Adelaide and Fremantle, replacing the smaller Marloo, which was transferred to the east coast route from Melbourne to Sydney, Brisbane and North Queensland.

Yongala proved to be the fastest ship yet to be placed on the Fremantle service, completing the sector between Adelaide and Fremantle in 3 days 16 hours.

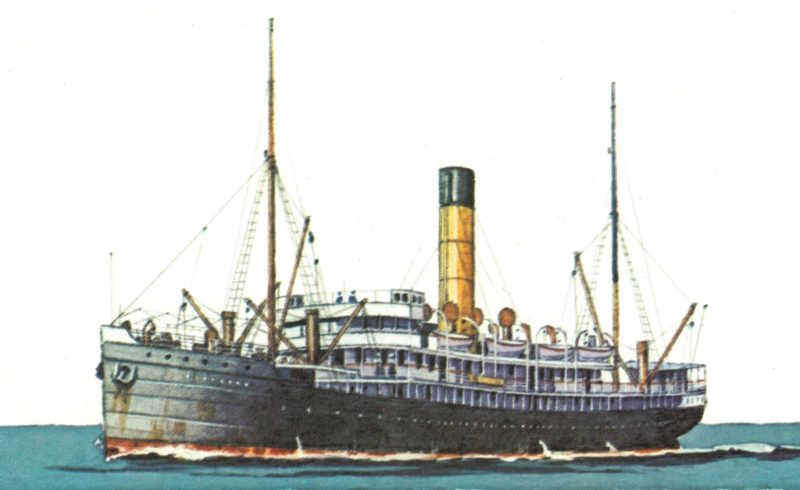

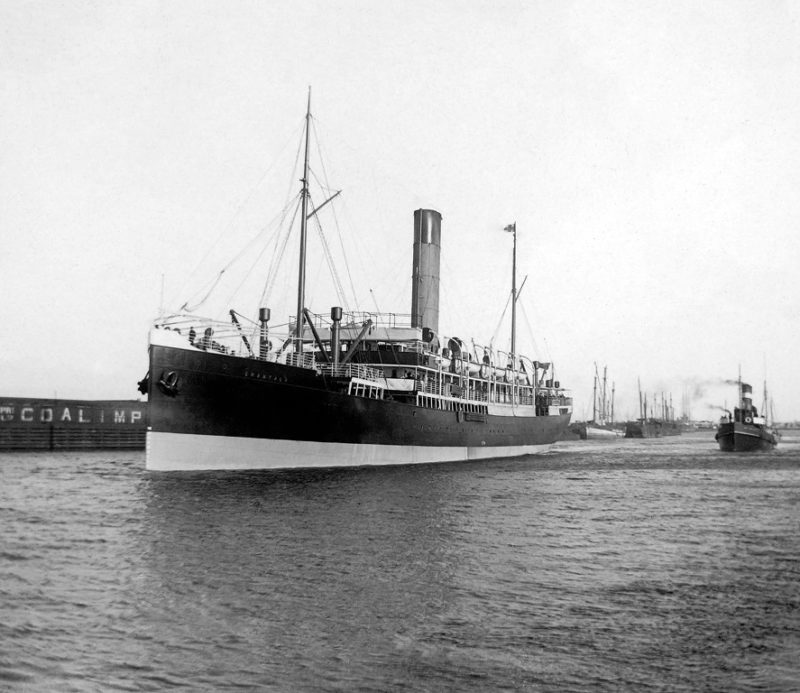

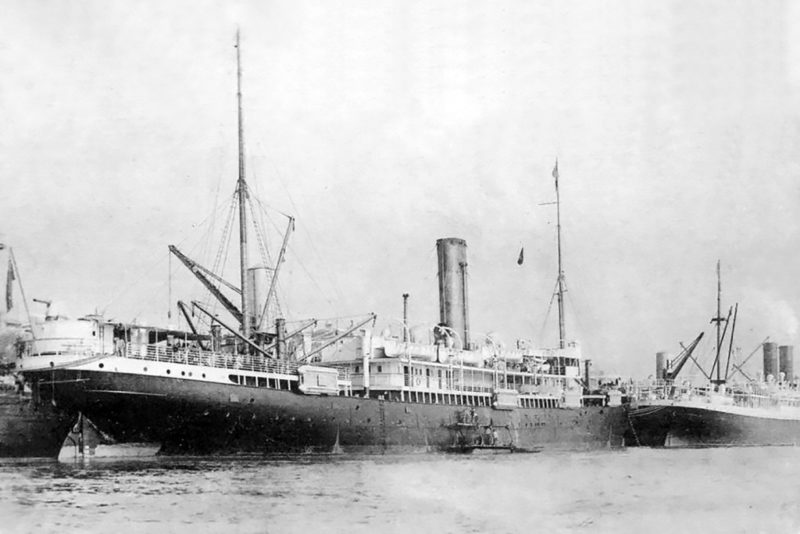

Meanwhile, the second ship was named Grantala, an aboriginal word for big, when launched on 28th May 1903, and fitted out in an identical way to Yongala. During trials on 23rd December a top speed of 16 knots was achieved, and the 3,655 grt Grantala was prepared for its delivery voyage to Australia.

Late in 1903 a British shipping company, the Houston Line, was attempting to break into the passenger trade between Britain and South Africa, but, not having enough ships of their own, had arranged to charter the brand new Manuka, built in Britain for the Union Steam Ship Company of New Zealand, to carry passengers to Cape Town on its delivery voyage in November 1903. The second voyage in December was taken by a Houston Line ship, but for their third trip the company chartered Grantala to carry passengers to Cape Town on its delivery voyage. However, before Grantala departed, the Houston Line had decided not to continue with the South African passenger trade.

Despite this, Grantala still embarked 200 passengers who had been booked to go to Cape Town along with some bound for Australia and left Southampton on 21st January 1904, under the command of Captain C. Dingle, arriving at Cape Town on 13th February. After disembarking passengers bound for South Africa more Australians returning home were embarked there and at Durban. With 223 passengers on board, Grantala proceeded directly to Fremantle, arriving on 29th February, and 28 passengers disembarked. On 3rd March the West Australian printed an interview with one of the returning Australians, which included the following:-

A gentleman formerly residing in Western Australia but who recently took charge of stud rams from Victoria to Natal, returned thence to this State in the ss Grantala, and gave a representative of this journal some of his impressions of the South African colony.

“My sojourn in South Africa,” he said, “was not of long, duration, and fortunately so, as South Africa did not strike me as being fit for an Australian to live in.”

“You evidently don’t think much of the country.”

“No; neither, for that matter, does any other Australian whom I met there, in fact, every one of them whom I spoke to is heartily dissatisfied with it, and with the rest of South Africa. The steamer in which I returned was packed with Australians glad to get away from it. We nicknamed the vessel ‘The Prodigal Ship’. All were disappointed with their experiences. Our boat came direct from Durban, and so keen was the booking that hundreds were disappointed in being unable to secure berths.”

Grantala arrived off Adelaide on the afternoon of 6th March, but did not berth, instead anchoring out for several hours while 14 passengers went ashore in tenders, and Captain Dingle was replaced by Captain J. Rees, who would be the regular master of the ship. The voyage continued to Melbourne, arriving on 8th March, leaving the same evening for Sydney, arriving on 10th March.

On 12th March Grantala left Sydney on its first voyage to Fremantle, replacing the Wollawra, which was transferred to join its sister Marloo on the east coast trade. Yongala and Grantala were only half the size of the new pair of liners built at the same time for the AUSN, the 6,942 grt Kanowna and Kyarra, but these four ships operated to a combined four-weekly schedule that provided a departure from Sydney and Fremantle every Saturday.

On the morning of 6th September 1905, as Yongala was crossing the Great Australian Bight on the way from Fremantle to Adelaide when, about 160 miles west of the Neptune Islands at the entrance to Spencer Gulf, a sailing ship was sighted almost on the southern horizon. Unable to read the signal flags that the vessel had hoisted, Yongala altered course to come closer and the signal stated ‘Loch Vennachar, please report me all well’. The 1,557 grt Loch Vennachar, owned by the famous Loch Line, under the command of Captain Hawkins, was on the final leg of a three month voyage from Glasgow to Adelaide and Melbourne, fully laden with general cargo including a consignment of 20,000 bricks.

Captain Rees of Yongala later stated that Loch Vennachar “presented a pretty sight as, with her sails in full standing, she sped along with every apparent prospect of shortly reaching port safely”. Yongala resumed its voyage and berthed in Adelaide the next morning, but when Loch Vennachar failed to arrive there in the next few days a search commenced. Eventually wreckage was found scattered along the south coast of Kangaroo Island, but there were no survivors from the 27 crew on board. Captain Rees later said he was extremely glad in the circumstances that he put the Yongala about and went toward the Loch Vennachar when he could not make out the signal. “Had I not done so”, he said, “I should probably be now wondering whether my omission to do so was not in some manner responsible for her loss”. It was an ominous portent of the fate that would befall Yongala just six years later.

With the addition to the Fremantle trade of the 3,540 grt Bombala of Howard Smith in 1904, and the 4,758 grt Huddart Parker liner Riverina in December 1905, the west coast service was reorganised under a joint scheduling arrangement between the various companies involved. Commencing in January 1906, Yongala and Grantala would extend their voyages to Brisbane, along with Bombala and Riverina, providing a departure every second week from the Queensland port. To better suit them for this service, Yongala and Grantala had a large section of their holds insulated for the carriage of frozen produce from Brisbane.

As the amount of gold being mined in Western Australia began to decline, so too did the number of passengers being carried on the service from the east coast, and the cargo trade was greatly diminished. In 1905 the companies involved in the Fremantle service decided that changes had to be made, and the Adelaide Steamship Company decided to place their two ships on an extended service that included Brisbane.

On 19th January 1906, Yongala arrived in Brisbane for the first time to inaugurate the new service from there to Sydney, Melbourne, Adelaide, Albany and Fremantle, and a special luncheon was held on board to celebrate the occasion. Yongala left Brisbane on 20th January, the 3,000 mile route to Fremantle being the longest the Adelaide Company had operated up to that time. Yongala was followed by Bombala on 3rd February and Riverina on 17th February, while Grantala made its first departure from Brisbane on 3rd March.

The extended service proved very popular with passengers in the summer months, but numbers fell off dramatically in winter. As a result, on 11th May 1907, Yongala arrived in Sydney from Fremantle and was transferred to the east coast trade, departing Sydney on 18th May for Cairns. On the return trip Yongala went on to Melbourne, which became the base port for the service.

On 15th June 1907, Bombala left Sydney for Brisbane followed through Sydney Heads sixteen minutes later by Yongala, also bound for Brisbane, and the pair began what was described in newspaper reports as, “a splendid ocean race which created a great deal of speculation and excitement among passengers and crew on their respective ships”. Throughout the next day the two ships were neck and neck, but on the evening of 16th June Yongala gradually was able to overhaul Bombala and passed Cape Moreton seven minutes ahead of its rival, having covered the distance from Sydney Heads in 30 hours 21 minutes at an average speed of 15.3 knots.

After almost two years on the east coast route, Yongala left Sydney on 13th March 1909 for Fremantle again. In early May the following item appeared in various newspapers:-

The Adelaide Steamship Company’s steamer Grantala, which hitherto has been employed in the trade between Sydney and Fremantle, via Melbourne and Adelaide, now is to be withdrawn from this run, and transferred to the service from Melbourne, to Cairns, via Sydney and Queensland ports. The Grantala will commence her new run on her return from Fremantle, leaving. Sydney on 29th May for Cairns. Her sister ship, the Yongala, will continue in the West Australian trade for the present.

This news was particularly welcomed in north Queensland, the Cairns Post reporting on 7th June:-

When it was learned that the Adelaide Company’s steamer Yongala, which for nearly two years traded between Melbourne and Cairns, had been placed on the West Australian run, much disappointment was expressed by the northern travelling public who were able to appreciate the benefits of a fast and reliable vessel. The Adelaide Company, however, recognising the importance of the trade of North Queensland, especially at the port of Cairns, decided to replace the Yongala by the Grantala, which vessel arrived here yesterday from Melbourne via ports.

Yongala would remain on the Fremantle trade for only a few months as in late August it was widely reported:-

An improvement has been effected in the social hall of the Adelaide Steamship Company’s liner Yongala. The apartment, which is a prominent feature of the vessel, has been re-upholstered and re-carpeted throughout, whilst the decorations have likewise been renewed. Extending almost the whole width of the ship, the social hall now resembles a magnificent drawing-room, and will no doubt meet with the appreciation of passengers. It is understood that after one more trip to Fremantle the Yongala will be withdrawn from the run, and transferred to the Queensland trade in which she was formerly employed. She will be succeeded in the West Australia service by the new 7,391 grt steamer Karoola, of McIlwraith, McEacharn line.

Departing Sydney on 28th August, Yongala arrived in Fremantle on 9th September on its last visit to the port. Departing on 11th September, Yongala called at Albany the next day, then berthed at Adelaide on 15th September and Melbourne on 17th September, arriving back in Sydney on 20th September. On Saturday, 25th September, Yongala departed for Brisbane and ports in North Queensland as far as Cairns, where she arrived on 4th October.

With Yongala and Grantala once again operating on the same service, the two ships were occasionally in either Sydney or Melbourne together, and once came a bit too close, as the Sydney Morning Herald reported on 1st July 1910:-

The Adelaide Company’s steamers Grantala and Yongala, which arrived yesterday morning, the former from Melbourne and the latter from Brisbane, came into mild collision at the Grafton Wharf. The Yongala, which was already berthed, was struck on the stern by the bows of the Grantala which Captain Sim was bringing in. The mishap was due to a sudden intensity of the strong wind that was blowing. The rail of the Yongala was broken, but there was little else noticeable. The damage could be covered by the expenditure of a few pounds.

With wireless being installed on most of the coastal passenger liners, equipment for Yongala and Grantala had been ordered from England which was on its way to Australia in March 1911, and was due to be installed in Yongala after its next trip. On 14th March 1911, Yongala departed Melbourne on its 99th voyage in Australian waters, under the command of Captain William Knight, who had 24 years of experience on the Australian coastal trades. There were 92 passengers on board, but only 2 were going to Cairns, the others disembarking at Sydney and Brisbane, where more passengers would embark.

Departing Sydney on 18th March and Brisbane on 21st March, Yongala arrived during the morning of Thursday, 23rd March at Flat-top Island, the anchorage for Mackay. Also on 23rd March the following item appeared in the Mackay Daily Mercury:-

Brisbane, Wednesday.

The following special weather advice was issued today: The new tropical depression has not moved any nearer to the Queensland coast since yesterday. There has been a steady increase in pressure along the Pacific slope, thus the atmosphere is very much intensified, and its influence is felt and reaches south from Cooktown, the weather being gloomy, unsettled and showery.

This was probably the latest weather report Captain Knight received before Yongala, after discharging 3 passengers and cargo, and embarking 2 passengers, departed at 1.40pm for Townsville, some 200 miles to the north. On board were 34 saloon and 31 second class passengers, 73 crew, and about 1,800 tons of cargo, including a large Lincoln bull bound for Cairns and a newly purchased racehorse named Moonshine, being taken to Townsville. At 4pm the same day, her sister ship Grantala left Townsville southbound for Mackay. About 6pm the lighthouse keeper on Dent Island at the entrance to the Whitsunday Passage watched Yongala go past, but that was the last time the ship would be seen.

During the night a fierce cyclone ripped through the Whitsunday Passage region, with the wind reaching a velocity of nearly 80 miles per hour, forcing ships in the area to seek shelter. Warned by a rapidly falling barometer, Captain Sim diverted Grantala to Bowling Green Bay, reaching there at 7.30pm to ride out the storm in sheltered water. At 8am the next morning the weather had moderated enough for Grantala to continue its voyage south, Captain Sim later describing it as one of the worst gales he had ever experienced. Among other ships affected, the Guthrie was able to anchor in sheltered waters, Captain Wilson stating later that this action saved his ship. The Taiyuan sheltered near Repulse Island and spent its worst night ever on the Australian coast, losing two boats during 12 hours at anchor.

Yongala was due to berth in Townsville early on the morning of 24th March, its failure to arrive at that time initially being put down to delays caused by the storm, and it was expected the vessel would turn up any time soon. As the hours passed it was still hoped that Captain Knight had taken his ship well out to sea to ride out the storm and it would soon come into the port. By 26th March three ships that had survived the storm had berthed in Townsville, but none had seen any sign of Yongala, which was posted missing the same day.

The steamers Tarcoola and Ouraka of the Adelaide Steamship Company were despatched with instructions to make a thorough search, but they found no trace of the missing ship. More vessels joined in the search, and the tug Alert located the first indications of a tragedy when wreckage identified as being from Yongala was found near Keeper Reef, about 25 miles NNE of Townsville. Shortly afterwards more fittings and some cargo were washed ashore in the vicinity of Townsville, proving beyond doubt that the vessel had met disaster.

Grantala had continued its voyage south, calling at Mackay on 24th March and going on to Brisbane, arriving on 27th March. It was only then that Captain Sim was informed that Yongala was missing. After Grantala arrived in Sydney on 30th March, a reporter from the Sydney Morning Herald had an interview with an unidentified officer from the ship, which was printed on 31st March, and included:-

“We cleared Townsville about 4pm, with a good southerly breeze; nothing out of the ordinary, just a good steaming wind. After rounding Cleveland the strength of the wind increased, and seeing that we were in for dirty weather the captain decided to shelter in Bowling Green Bay till the worst should blow over, though even then we did not expect the hurricane that turned up during the night. We had a fair glass, and were not at all concerned.

The worst of the hurricane struck us between 1 and 2 in the morning, at which time the Yongala should have been somewhere in our vicinity, allowing for the time she passed Dent Island. To give an idea of the sort of weather we went through that night, when we were sheltering in Bowling Green Bay, only five miles from the powerful light on Cape Bowling Green, we could not catch a glimpse of the light, so thick were the rain squalls. Our own vessel rode out the storm excellently, and we had no fears about the Yongala, and knew nothing about the disaster until we reached Brisbane, when, as we passed the pile light, they signalled us to know if we had seen anything of the Yongala. I tell you it sent cold thrills down our spines when we heard she was missing.”

As to the stability of the steamer he held no uncertain opinion. “It is absurd”, he said, “to question the stability of either the Yongala or our own vessel, which are identical in every respect. Finer sea boats it would be hard to find”.

Numerous theories were advanced regarding the fate of Yongala, and at the inquiry into the vessel’s disappearance the court said that any statements concerning its movements after passing Dent Island could only be regarded as conjecture. The court did find that in construction, stability, and seaworthiness, Yongala was equal to any vessel of its class on the Australian coast. It was generally agreed that the vessel had foundered somewhere NE of Cape Bowling Green and probably within 30 miles of Townsville.

The wireless equipment for Yongala and Grantala that had been ordered from England arrived in Australia soon after Yongala was lost, and was quickly installed in Grantala, as the Brisbane Telegraph reported on 30th May:-

At the time of the loss of the Adelaide Steamship Company’s line flagship Yongala, whose mysterious disappearance, with all on board, plunged all Australia into grief a couple of months ago, the necessity of’ equipping even our coastal vessels with wireless telegraphy outfits was pointed out in these columns more than once. The owners of the lost vessel also were seized of the importance of such an innovation, and their steamer Grantala, which arrived here on Monday after an extensive overhaul, now possesses one of these most useful of modern nautical apparatus. She thus is the first coastal steamer employed in the Queensland service to receive such an installation.

The loss of Yongala had the inevitable effect on the patronage on Grantala for a while, but by the end of 1911 the ship was again operating with good passenger loadings and cargo. Over the next three years Grantala maintained its regular schedule without any major incidents. On 7th July 1914 Grantala departed Melbourne on a regular voyage north, leaving Sydney on 11th July, and visiting the usual ports as far as Cairns, returning to Sydney on 29th July.

Instead of continuing to Melbourne, Grantala remained in Sydney, being berthed there when war was declared. Grantala had been advertised to depart Sydney on Saturday, 8th August for Queensland ports, but on 7th August the vessel was requisitioned for conversion into Australia’s first hospital ship to accompany an expeditionary force being raised to capture German New Guinea.

The British Admiralty had devised a scheme whereby, in the event of war breaking out with Germany, merchant vessels could be converted into hospital ships in various ports around the world, one of which was Sydney. In July 1913 the materials needed for this conversion work, including iron swing cots, blankets, sheets, hospital crockery, drugs, dressings and a complete hospital laundry, were sent to Sydney. It was placed in storage at the Royal Australian Navy base at Garden Island in Sydney Harbour, where Grantala was sent to have the medical equipment installed, which took three weeks.

Passenger lounges and dining rooms were converted into wards fitted with swinging iron cots. Most of the cabins had their doors removed and were fitted out for two patients, and two cabins were padded for patients with mental illness. One saloon could be used as a lecture theatre and adapted to hold forty cots. The poop deck was fitted out as an infectious diseases ward, with a timber roof, and some upper deck areas became open-air wards with iron beds surrounded by screens, particularly suited for patients with tuberculosis which thrived in the conditions onboard warships at the time. The wards could accommodate 180 patients, though if necessary the number could be increased to 300.

A steel structure was built by navy engineers from Garden Island over the hold on the after well deck and fitted out as a fully equipped operating theatre, and there was also an X-ray room. A laundry with a steam disinfector and steriliser was fitted in No. 2 hold, and two sanitary wash places were erected in the open air for the emptying of bedpans and urinals. A lift was installed at the stern to connect the various decks to ease the movement of patients.

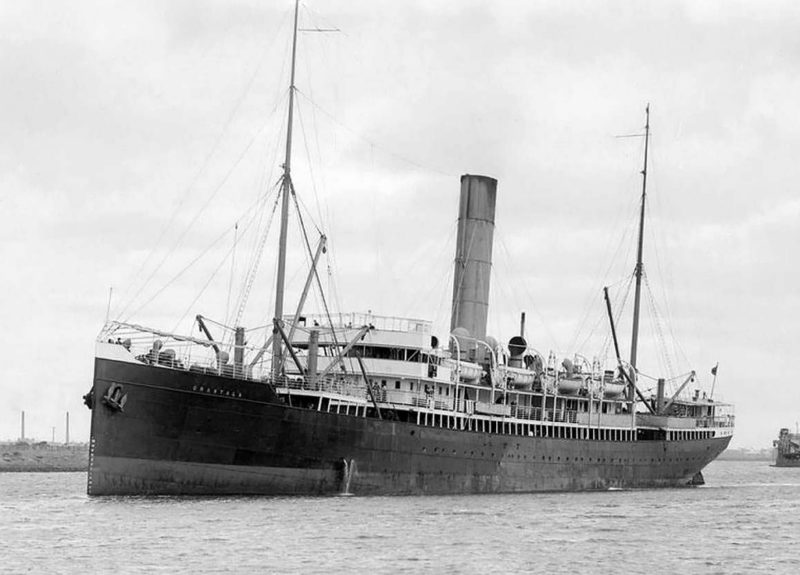

Designated Australian Hospital Ship No VIII, in accordance with Hague Convention rules Grantala was painted white with a yellow funnel, a green band round the hull and large red crosses were displayed on both sides.

Classified as a Merchant Fleet Auxiliary, Grantala flew the Blue Ensign of the Royal Naval Reserve. Acting Fleet Surgeon Dr. W.N. Horsfall, recently retired from the Royal Navy, was appointed Principal Medical Officer, and a civilian medical staff recruited from the Royal Prince Alfred Hospital in Sydney, which included 7 surgeons and male sick berth attendants along with a matron and 6 female nursing sisters. A full merchant navy crew was appointed to the ship, which was placed under the command of Captain H.E. Brissenden, and this caused some initial problems until areas of responsibility between the medical staff and ship’s officers could be organised.

Grantala departed Sydney on 30th August bound for Townsville, but the next day 15 of the Sick Berth staff refused to clean some paintwork, stating they had volunteered to nurse the sick and wounded and not to clean paintwork. Dr. Horsfall advised them he would have them sent back to Sydney when the ship reached Townsville, which brought them to their senses, and Horsfall had no more trouble with the medical men. Instead of continuing the voyage north as soon as possible, Grantala did not leave Townsville until 8th September to join the expeditionary force that was already en-route to Rabaul in German New Guinea.

The troopship Berrima, carrying one thousand troops, was escorted by a strong naval squadron led by the battle-cruiser HMAS Australia along with several cruisers and destroyers as well as 2 submarines. On 11th September a small force was landed near Rabaul to capture a wireless station the Germans had set up in a village called Bitapaka, which was several miles inland. While proceeding up a dirt road the force came under heavy fire from local troops commanded by German officers, this being the first action between Australians and Germans in the war, and six Australians were killed before the wireless station was captured. This became known as the Battle of Bitapaka, and is of great significance to Australian military history in the First World War.

On the afternoon of Saturday, 12th September, the troopship Berrima berthed at the Rabaul jetty, a force was sent ashore and fortunately occupied the town without any opposition, following which HMAS Australia and the other Australian warships then anchored off Rabaul.

On the morning of Sunday, 13th September, the ship’s company on Grantala was assembled on deck for a church service when a vessel was sighted coming towards them. Sister Kirkcaldie later recounted, “We noticed on the far horizon a tiny dot that even as we watched drew swiftly nearer. The Padre, conscious of a distracting rival to his sermon, cut it abruptly short and, released, we crowded to the rail. A shot across our bows brought us to a standstill and a moment later HMAS Yarra circled around us. A swift scrutiny satisfied her as to our identity and she disappeared into the distance.

The morning was wet and foggy, the kind often experienced during the rainy season in the tropics, and it was only as we crept well into the harbour that one by one we recognised the ships of our small Australian Navy lying at anchor. Gradually the news of its doings filtered through to us. Even though we were actually on the field of action it was only in fragments and by word of mouth as boats visited us that we learned the tale of the last twenty four hours”.

When Dr. Horsfall boarded HMAS Australia and reported to Admiral Patey, in command of the expeditionary force, he was immediately asked why Grantala had not arrived the previous afternoon, as had been requested in a signal sent several days previously. Horsfall knew nothing of this signal, and when he returned to Grantala learned that a signal had been received a day or so before, but it had been in naval code and the wireless operator, a civilian, was unable to decipher it. Had the Expeditionary Force sustained heavy casualties during the landings the previous day, Grantala’s late arrival might have proved disastrous.

Shortly after arriving, Grantala received its first patients, including two sailors with gunshot wounds inflicted during the previous day’s action. Sister Kirkcaldie described the initial number of patients as being relatively small, with some suffering from gunshot wounds to limbs. The medical officer’s journal recorded that ten sailors from HMAS Australia and two soldiers from rifle companies were admitted as inpatients.

With German New Guinea firmly under Australian control the naval ships soon left Rabaul, but Berrima remained tied up in Rabaul, and Grantala remained at anchor in the harbour, receiving an occasional new patient. However, the attention of the Royal Australian Navy had turned to locating and destroying the two major German naval units that had been based in the Pacific, the battle-cruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, under the command of Admiral von Spee. When it was believed they were attempting to escape by heading towards South America, HMAS Australia and the other major ships were ordered to make Suva in Fiji their base for finding the German ships,

By the afternoon of 4th October only the hospital ship Grantala was left in Rabaul Harbour, but the next day she also left for Suva. For the next two months Grantala swung at anchor in Suva Harbour, but the number of patients remained very small. On 8th December, in an epic battle off the Falkland Islands, Scharnhorst and Gneisenau were both sunk by a British fleet, and the German naval threat in the Pacific was finished.

Grantala returned to Sydney on 22nd December, and was chartered by the Australian Government to search for the missing trawler Endeavour, which was on charter to the Government to exchange personnel at Macquarie Island. Endeavour had left Macquarie Island on 3rd December and should have arrived back in Hobart five days later, but had disappeared. Still in hospital ship colours, Grantala left Sydney on 29th December and headed south to join other vessels already involved in the search. On Saturday, 16th January 1915, Grantala arrived in Hobart, and on 18th January, the Hobart Mercury reported:

A somewhat unexpected arrival at Hobart on Saturday was the Adelaide Steamship Company’s steamer Grantala, which is under charter to the Federal Government to search for the missing federal trawler Endeavour. The Grantala, which has put into Hobart for coal left Svdney on Tuesday, 29th December last to carry out a search for the Endeavour in an area specified by the Navy Office. Macquarie Island was visited on Tuesday, 12th inst, and departure made on Wednesday, 13th inst, for Hobart. The following morning a large iceberg was sighted.

Throughout the voyage the prevailing winds were westerly. Gales accompanied by thick weather were frequent. The vessel carried out the search over an area of 600 square miles and experienced very heavy weather. No sign of the missing vessel was seen. The Grantala sails on Wednesday to continue the search.

Throughout the search a man was permanently kept in the crow’s nest day and night, after dark two 500-candle power electric lights were shown at the masthead, and at 10 o’clock every night a rocket was fired, but there was no sign of the missing vessel. Grantala returned to Hobart on 5th February, then went back to Sydney, arriving on Tuesday, 9th February, and next day the Daily Telegraph reported on the voyage after the ship left Hobart on 20th January:-

She proceeded to the Snares, a group of small islands about 60 miles SSW of Stewart Island. A thorough search was made there, but without result and a course was then steered to the Antipodes Islands, which lie south-east of New Zealand, and the Bounty Islands.

The next land sighted was the Auckland Isles, which are likewise uninhabited, though occasionally visited by whalers. The Auckland group has been the scene of many a tragic shipwreck. The night was passed in the shelter of Erebus Cove, and next day the Grantala circumnavigated the Islands, a careful watch being kept upon the shore. The vessel left the group on Sunday week, and returned to Hobart. The voyage was uneventful, though strong south-westerly gales, with heavy seas and fog, were experienced. This second cruise occupied 16 days.

The Grantala left Hobart on Sunday, and came straight to Sydney. Captain Brissenden stated on arrival that he saw no sign of wreckage whatever. The Grantala will be refitted, and will re-enter the coastal passenger trade.

Soon after arriving in Sydney Grantala was released from Government control and handed back to the Adelaide Steamship Company. Following an extensive refit, Grantala returned to the east coast trade with a departure from Sydney on 10th April 1915, arriving in Brisbane two days later and suffering a minor mishap, as the Courier reported:-

After an absence of many months the Grantala, of the Adelaide Steamship Co., arrived from Sydney yesterday. The vessel will be regularly employed in the company’s Melbourne to Cairns passenger and cargo service. The Grantala is in command of Captain Brissenden. When approaching Kangaroo Point about midday the Grantala was assisted by the tug Coringa. The two vessels came slowly up the river against an ebb tide, and on nearing the wharf of the Brisbane Wharves Ltd., it was noticed that the Grantala’s engines were put astern. The port anchor was let go, and the tow-line then parted. The Grantala slowly approached the wharf, the stem striking the structure, doing trifling damage. The vessel eventually got clear, and resumed the passage up the river to tho Adelaide Steamship Co.’s South Brisbane Wharf.

In late July there were reports that Grantala was to be switched to the Sydney-Fremantle service in late August to replace Warilda, which had been requisitioned for military duty. However, on 14th August the Melbourne Herald reported:-

Today the Adelaide SS Co.’s interstate liner, Warilda, is leaving Fremantle on its last trip in the interstate trade, for the present. On arrival at Sydney the vessel is to be withdrawn from the running, and its usual monthly trip will be done by the Melbourne SS Co.’s Dimboola. Another change in the interstate service is the substitution of the Adelaide Co.’s Gulf steamer, the Rupara, for the Grantala in the Melbourne-Cairns run.

Grantala had departed Melbourne on 27th July on what would ultimately be its final voyage on the Australian coast, arriving in Cairns on 8th August, leaving on 11th August for the south. On 19th August Grantala arrived in Sydney and the voyage was terminated. Soon reports began appearing that Grantala had been sold to unidentified ‘eastern buyers’ and would be leaving Australian waters within a few weeks. The vessel remained in Sydney Harbour, then on 23rd November 1915 she was sold to the Red Funnel Shipping Co., of London, a British subsidiary of the French company, CGT, better known as the French Line.

On 4th December, Grantala left Sydney for the last time, and after a call at Fremantle, headed for Cape Town, then went on to Naples. She arrived at Bordeaux on 28th March 1916. She was renamed Figuig, after a town in Morocco on the border with Algeria, and was placed in service across the Mediterranean from Marseilles to Algiers. In 1921 the French Line purchased the vessel under their own name, and it remained in their fleet until May 1934, when she was sold to M. Bertorello shipbreakers at Genoa.

The final resting place of the Yongala remained a mystery until 1958, when the wreck was discovered about eleven miles off Cape Bowling Green, lying on its starboard side with an anchor out. It is generally thought that Yongala, unable to reach the safety of Bowling Green Bay, must have capsized while trying to turn into the wind with the assistance of the anchor. The ship’s bell was brought up and is now in the Townsville Maritime Museum along with other items.

Over the years the wreck became covered with seaweed and other growth, and it was hard to recognise many features. When Cyclone Yasi swept through the area in February 2011 there were fears it had badly damaged or even destroyed the remains of Yongala, but when divers returned to the wreck they found some areas of deck had collapsed, but otherwise it was still intact. The most amazing thing was the way the storm surge had removed much of the seaweed and other growth from the hull of the ship, and it is now much easier to locate the main features.

Today, Yongala is the most popular wreck dive site in Australia, though access is strictly controlled. Located 90 miles from Townsville in the world heritage listed Great Barrier Reef Marine Park, and protected under the Historic Shipwreck Act, the remains of Yongala are rvery well preserved.

The vessel lies 27 metres down, the highest section of the port side being only 15 metres below water level. This makes the wreck easily accessible for qualified divers, and the water is extremely clear. As there are no reefs near the wreck it has become a home for many species of marine life, which adds further interest to the dive.

Comments

Sorry, comments are closed for this item